In January 1879, the Columbia River froze, blocking off much of the mail service to the north, including Thurston County. Residents in the County hunkered down by their wood stoves and fireplaces, waiting for the weather to change. Although not the area’s coldest winter on record, there were a rough few weeks of chill.

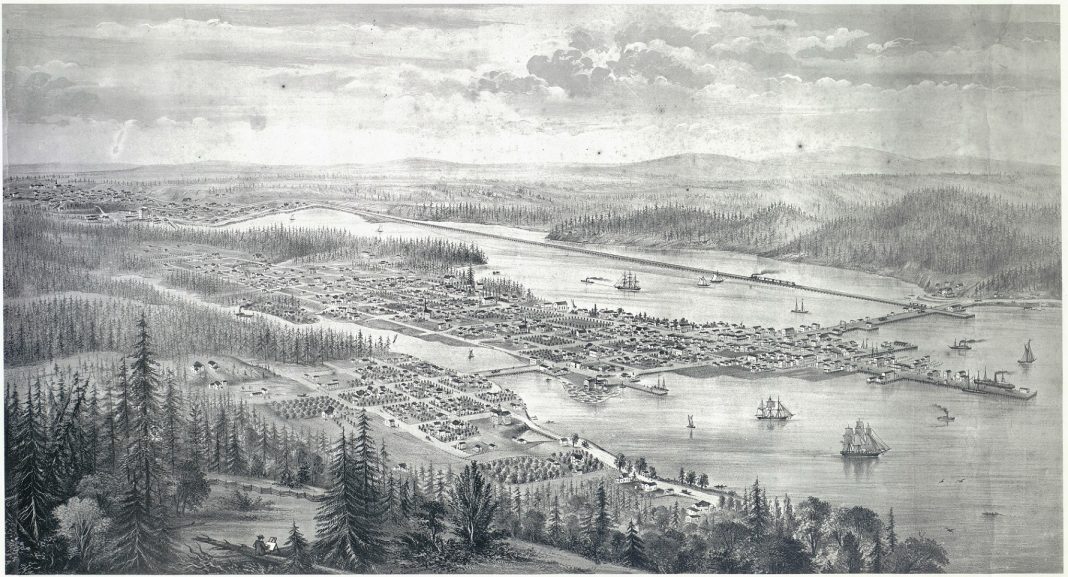

Thurston County was a fairly new entity in 1879. Only 27-years-old, the County was beginning to transition from a frontier town into a modern society. The economy of Thurston County was based on the outdoor work of farming and logging, and the newspapers thus made frequent references to the weather.

The summer of 1878 was a hot one. Olympia and other towns around the Puget Sound banned fireworks because of the danger of fire. By mid-August, smoke from wildfires had grown so dense that the Olympia Transcript newspaper remarked that “the smoke on the Sound is getting quite dense, from fires in the surrounding woods, with the prospect of soon being an impediment to navigation.” Some of the smoke came from a severe fire in a logged off area at the head of South Bay.

While complaining of dusty roads, the farmers got to harvesting and threshing their grain as summer ended. But the fires lingered into September. On September 21, the “Olympia Transcript” observed: “The nights are getting quite cool and but for the smoke and fog we would have heavy frosts.”

The fall was warm and rainy. There was a county fair in October. Colder weather brought a diphtheria epidemic that lasted for months. Late fall and early winter brought heavy rains and the occasional wind storm, nothing unusual for that time of year.

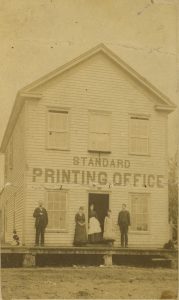

Christmas passed peacefully. The “Washington Standard” praised Olympia’s behavior, observing on January 4, “‘What a still holiday season’ is a common remark among our people, and quite a consistent one it is. Thus far, we have had to record no case of hoodlumism, no demonstration of intemperance, or ungainly demeanor. Everybody is quiet, lovely and happy.” Businesses had done well during the holidays and the newspaper cheerfully remarked that the steam meat-cutting machine at the Chambers & Son’s Market had been working full time to prepare meat for sausages and meat pies.

Frigid weather finally arrived. The coldest temperature of the year, 19 degrees above zero, was recorded on January 1 and the first snow of the season came on January 4. Clear skies kept the cold around and people woke up to frosty windows and ice in their water jugs.

The “Washington Standard” reminded people to keep warm by piling on blankets and warned them to remember to watch their fireplaces and stoves to prevent fire. Olympia’s wooden sidewalks became slippery (more so after children poured water on them to slide on). The freezing caused water pipes to burst and stores sold large amounts of sawdust to use as insulation for pipes. Cougars and wildcats were coming down from the mountains and people were urged to keep watch on their livestock and chickens.

Another pressing concern was that the Columbia River had frozen over, blocking the normal mail delivery from Portland that brought letters and packages from California and parts of the East Coast to Washington. The Olympia Post Office shelves were getting bare. The river would remain blocked for much of the month. Also local steamships, historian Gordon Newell noted in “Rogues, Buffoons and Statesmen,” had to avoid ice from the Deschutes River and were unable to fill their boilers with water because of problems with the water tank on Percival’s dock due to icy leaks farther up the line.

Still people found ways of enjoying the cold. The clear skies made for lovely stargazing (due to less light pollution, the Milky Way would have been visible in the city). People bought ice skates from local hardware dealers and some children even skated on “Capitol Pond,” a small body of water presumably near the territorial Capitol.

Snow fell once more, but it soon turned to rain, though there was a foot of snow in the nearby Black Hills. More seasonable weather of rain and sunshine returned at the end of the month. Native Americans returned to Olympia with canoes full of oysters to sell. The Columbia River thawed and the “Washington Standard” joked about “oceans” of mail now swamping the Olympia Post Office.

The thaw came at the same time as the highest tides of the year, which left the “Washington Standard” office feeling like Noah’s ark surrounded by water. But spring was coming. By early February, muddy roads had turned to dust and the “Washington Standard” celebrated that “weather prophets hail with delight the daily increasing number of robbins [sic].” The next winter, however, would be another cold one, with the Columbia River freezing again. The winter of 1878-1879 in Thurston County may not be a “Great Cold,” but it was a cold one. It is an excellent window into what life was like in an era without central heating.