Certain land features or road configurations may look curious at first glance, but there is usually a story behind the clues. The neighborhood along Budd Inlet in West Olympia still shows evidence that it almost had a railroad running right through it, one that was supposed to connect Olympia to Port Townsend. It was an option business investors were pondering that would likely have changed everything about this quiet area. The story of how the idea emerged, and why it did not evolve, is part of the more extensive railroad transportation history in Olympia.

A disconnect, or rather, an awkward connection, existed between Olympia and distant cities. In a land of very dense forest with difficult roads, commerce and travel still depended on rails and waterways for transport. Development and solutions to make connections smoother for people and business were explored. Budd Inlet afforded Olympia a port, but the deep water needed for large cargo ships and big passenger ferries was not immediate to the downtown waterfront area. The city of Olympia was informed that the inadequate depth nearest the city would not allow for large steamships. Necessity spurred the construction of a receiving area out where the deep water was. This was the genesis of Brown’s Wharf, which was at the edge of today’s Old Port neighborhood.

A disconnect, or rather, an awkward connection, existed between Olympia and distant cities. In a land of very dense forest with difficult roads, commerce and travel still depended on rails and waterways for transport. Development and solutions to make connections smoother for people and business were explored. Budd Inlet afforded Olympia a port, but the deep water needed for large cargo ships and big passenger ferries was not immediate to the downtown waterfront area. The city of Olympia was informed that the inadequate depth nearest the city would not allow for large steamships. Necessity spurred the construction of a receiving area out where the deep water was. This was the genesis of Brown’s Wharf, which was at the edge of today’s Old Port neighborhood.

In 1875, John French and B.F. Brown built Brown’s Wharf. There, passengers from incoming steamships could be rowed to Olympia. Cargo as well, could be brought to Percival Landing given the height of the tide. In a symbiotic relationship, Brown and French had a place to load the timber that they had cut and hauled, and larger ships had a place to deliver or receive passengers and cargo via smaller boats. With a deep-water wharf in place, the prospect of laying railroad track to it was enticing.

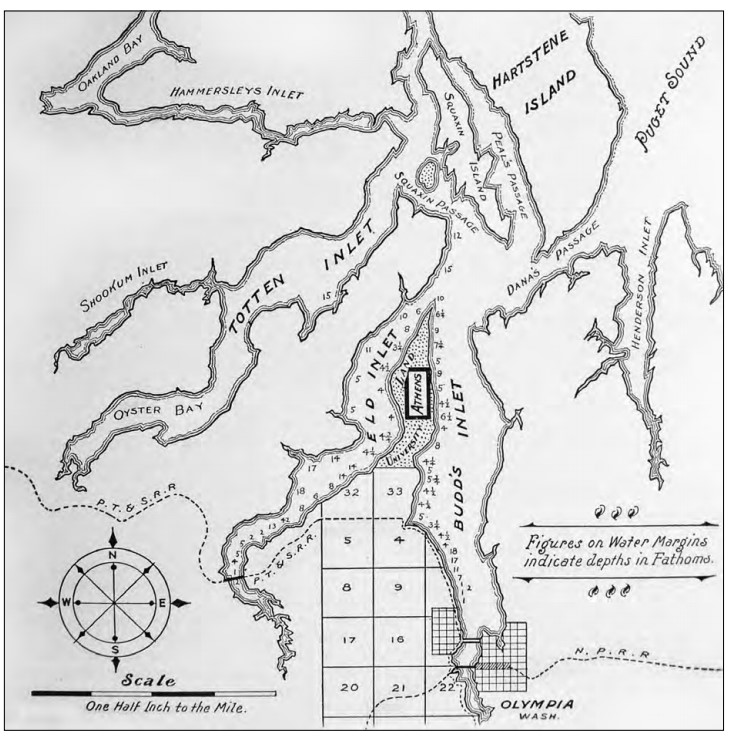

The Olympia Tenino Railroad began in 1878, and a spur line was extended north from Olympia along the west side of Budd Inlet. The plan, of those financially interested, was to continue that rail line from Olympia, north along the west side of Budd Inlet, on to Union City at the Hood Canal. From the there it would go on to Quilcene and then another 27 miles to Port Townsend. Ultimately, this would connect Port Townsend in the north to Portland, Oregon in the south.

Olympia stood as an axis point between many places. The city considered three separate proposals, all at one time, from those who wanted to run rail through town. Union Pacific wanted a path between Seattle and Portland. Grays Harbor Railroad wanted a connection between Grays Harbor and Tacoma. The Oregon Improvement Company wanted to connect its Port Townsend Southern Railroad to its Olympia Chehalis Railroad (formerly the Olympia Tenino line). Each faction wanted yard and depot land, rights of way, and each wanted $50,000 in cash. Olympia’s benefit for doling out cash and land? All of the access to commerce. Olympia agreed to all three proposals.

The Oregon Improvement Company’s project to lay rail between Olympia and Port Townsend would pass through a few places we see on the map today. The Olympia-Tenino narrow gauge came up from the south, and the proposed project would have it widened and continuing up through Buter’s Cove. Butler’s Cove was a popular destination for picnics and camping. Even the plan for a utopian community at nearby Athens was in the planning phases. The Butler’s Cove location and other commercial interests made it appealing due to an increasing interest in exporting coal from the very useful deep-water site. The cove was chosen as the turning point where the tracks would then take a northwesterly path across Mason county, avoiding estuaries, toward the Hood Canal.

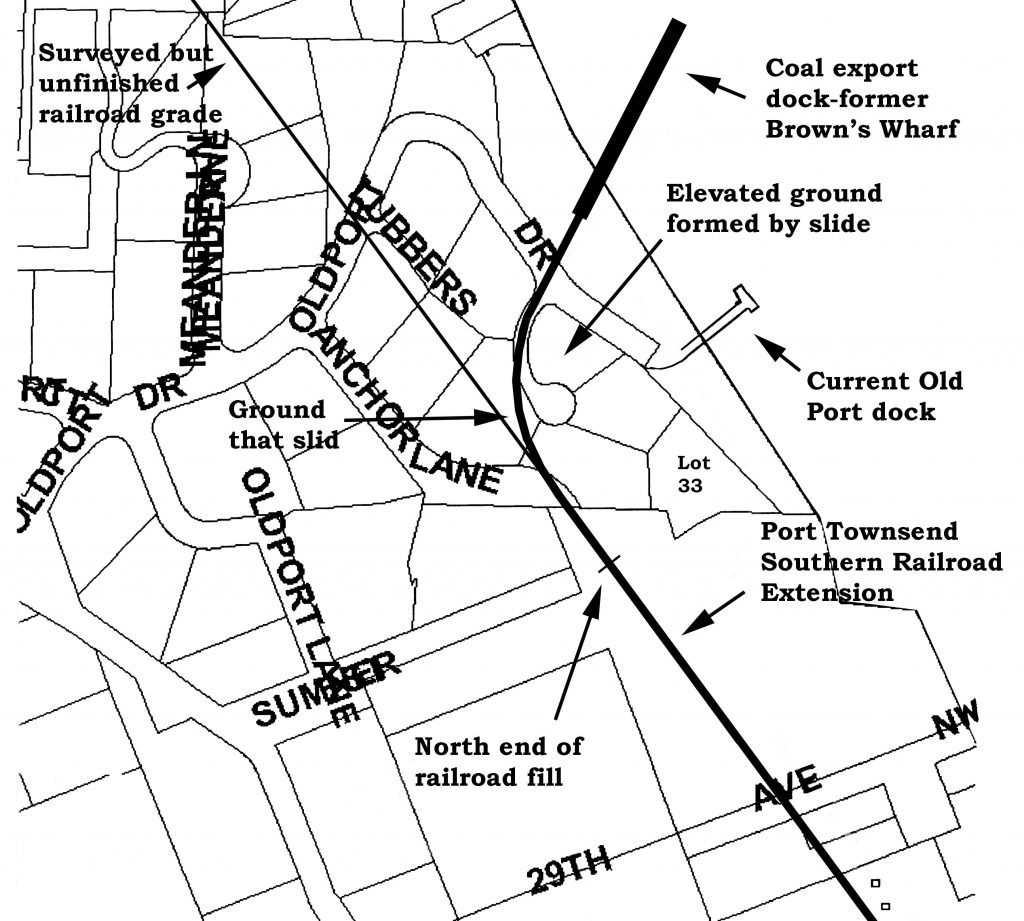

Clues indicating past railroad plans are visible on the west side of Olympia. From West Bay Drive, the grade which was prepared to support the tracks can still be seen. It rises up along the western bank of Schneider Hill Road. The grade can also be observed along 25th Avenue where it travels north and south parallel to Budd Inlet. Where 25th Avenue curves west, the grade continues north through the woods. Old Port has a new dock, but just to the north is where Brown’s Wharf once stood.

Economic difficulties of the time, availability of coal commodities, a worker strike and the state of financial backings all led to the project not coming to fruition. The city of Olympia reached its arm out to deep water with a long wharf in the later 1880s, and the Army Corp of Engineers dredged the channel in the early 1890s. Both actions lessened the need for a deep-water port out at Brown’s Wharf or a railroad through it to the north. In the end, we see how it all turned out for the west side, Old Port, Butler’s Cove and the rest. How different life would have been.