“You are always a penguin, no matter where you go in life!” For the 320 elementary students at Parkside Elementary School in the Tenino School District, school principal Brock Williams embraces the school mascot and shares his enthusiasm with his students and the community. Williams, a school district administrator in Tenino since 2000, grew up in Tenino, following in the footsteps of his father Hal Williams, also a school principal, and his mother, Shirley Williams, an elementary school teacher.

![]() In a family of educators, you would think Brock Williams would have been a confident student, but he had a secret—he struggled to read until fifth grade.

In a family of educators, you would think Brock Williams would have been a confident student, but he had a secret—he struggled to read until fifth grade.

“I have dyslexia,” Williams said, a computer in his hands. “Even now I have a program on my computer that will read aloud an email or a text to me. I am reading it too, but the kind of reader I am, it helps my comprehension if I use a few different strategies.”

A generation ago, reading instruction included time called Silent Sustained Reading, or SSR. Williams acknowledges for students who are naturally gifted readers, SSR encourages students to read at their grade level or even beyond. For him, though, he was able to hide behind the covers of a book, pretending to read by running his finger along the words and turning the pages when he saw the teacher watching him.

“Thank goodness for my mom,” Williams shakes his head. “She knew I couldn’t read, so she got creative. She was ahead of her time. She would record programs from the radio. When I got home from school, we would listen to ‘The Lone Ranger’ and ‘Superman’ together and she would quiz me on the characters and the story. I didn’t know it, but she was working on my reading comprehension—just without the words.”

Dave Whitmire, a fifth grade teacher, helped Williams with his reading. When copiers replaced Xerox machines, one teacher would give Williams a photocopy of a chapter to read. By having the copy ahead of time, he could memorize his section. Instead of feeling worried he was able to follow along with the others and read his part. It took time, but with the use of strategies and the support of his parents and his wife Heidi, Williams graduated from Central Washington University with a bachelor’s degree in education and a master’s degree in education administration.

So when Williams began thinking of new ways to reach the struggling readers in his school, he got the idea from “March of the Penguins.” Just like the movie where the penguins maintain their slow-but-steady march to their winter home, Parkside students, some living in the cycle of generational poverty, started on their own journey—with a difference.

“Students need to read out loud to someone who cares. I don’t want them hiding behind a book cover like I did. At Parkside, we have adults waiting to read with kids before school, during lunch, and after school. If a child wants to read, someone will listen.”

Colleen Taylor, Title 1 teacher and school librarian at Parkside, is often Williams’ planning partner for a new initiative with their young students. “I’ve known Brock since he was a teacher in the district. Sometimes parents resist reading interventions for their student, and he will say to them, ‘Do you think I am a good reader?’ Then he tells them his story of struggling to learn to read. He cares for each student but he also sees the big picture. It is his goal that 100% of our students leave our school reading on grade level. I don’t think he’ll stop until it happens.”

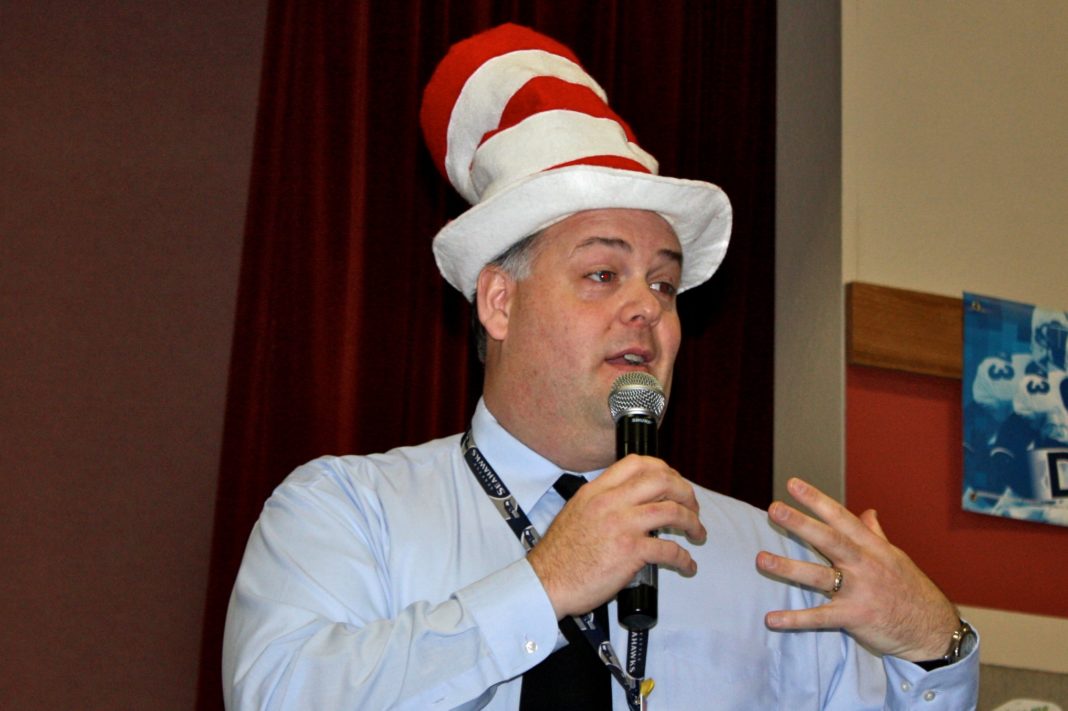

Williams knows there are other life skills children must develop as they mature. Each Friday he invites students to have lunch with him. At their morning assembly, he asks them to introduce themselves using his microphone. Some are too shy while others jump to try it. He stays with the shy ones. He knows it is just a matter of time.

“Brock Williams is an impressive person,” Bobbi Quentin, another Parkside staff member comments. “There is nothing he will ask someone to do if he hasn’t done it himself. He is on the sidewalk before school and after school greeting students. He knows their names, their brothers’ and sisters’ names. He fills in at the crosswalk, mops the floor, he’ll do anything. He respects his staff and we respect him.”

Almost 60 percent of Parkside’s population is designated free and reduced lunch. Williams is beginning to see some of his old students come back—this time as parents. “The fact that some of the young parents bring their students to school shows that we have already improved. They are more successful parents than a generation before. They want to help their students and reading is the most important skill to have. I tell them to read, read, read. Play books on tape, have conversations.”

Williams knows what it is like to feel frustrated about learning, but he tells a story that changes everything. “When I was in college, I took a special education class. I found myself.” For a successful educator responsible for the children in his school, his simple declaration says it all.

“Everyone learns differently,” Williams said. “Adults need to be willing to improve themselves too. Try. That is the best you can do. Try to improve yourself.”