It would have been much more natural to leave from the back door. And, if they had, Arthur J. Thompson and his wife would have died.

But instead, when he heard a terrifying scream on the early evening of Saturday, April 4, 1942, Thompson and his wife left from the front door as a U.S. Army P-38 crashed into a bluff in their backyard, killing the pilot and smashing the plane into thousands of pieces.

But instead, when he heard a terrifying scream on the early evening of Saturday, April 4, 1942, Thompson and his wife left from the front door as a U.S. Army P-38 crashed into a bluff in their backyard, killing the pilot and smashing the plane into thousands of pieces.

Not even four months had passed since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into World War II. The Japanese navy was still on the march across the Pacific and the American victory at Midway was not even on the horizon for people like the Thompsons. While they likely kept up with the news of the war, their day-to-day experience of the war in their backyard had to do with the sounds of the 55th Pursuit Group now stationed at the Olympia Airport.

The airport added a modern hangar and paved landing strips in the early ‘40s, and had turned its sights on the looming war. The airport, paired with classes held at St. Martins College, was a site of the Civilian Pilot Training program before the war.

Officially a satellite operation of the Army’s McChord airfield, it also served as temporary home for units such as the 37th Flying Training Squadron. The 37th was first outfitted with P-43 Lancers before later transitioning to P-38 Lightning interceptors. The unit was first activated at an airbase in the San Francisco Bay area, then trained on their way up to the West Coast to Olympia before heading off to England.

The P-38 (or technically the P-38E, the particular variant of the P-38 that crashed into the Thompsons’ yard) was probably one of the most recognizable of World War II aircraft. Described as “two planes, one pilot,” it featured two fuselages carrying engines set equidistance along the wing with a separate pilot fuselage in the middle. The well-powered P-38E was the first version of the aircraft that was specifically designed for combat and started rolling off the Lockheed assembly line only two months before Pearl Harbor.

Because the P-38 was big, it also had to be powerful. At 10 tons, the P-38 was near twice the weight of the other ubiquitous World War fighter, the P-51 Mustang.

But the large size and overpowered engines needed to get the Lightning flying would end up being its undoing. The early P-38s that served in Europe (like those flown by the 37th) consistently threw rods, swallowed valves and had other mechanical issues, sometimes even having catastrophic failures.

In the end, the judgment on the Lightning was that is was a very effective plane, but only when handled by a well-trained pilot. Everyone wanted to fly it because of its power, size and speed, but few were experienced enough to handle it. In fact, one survey of pilots beginning training found that 87 percent of new students wanted into the P-38.

It was also a complicated plane compared to most other available single-engine fighters.

“After flying the P-38 for a little over 100 hours on combat missions, it is my belief that the airplane, as it stands now, is too complicated for the ‘average’ pilot,” said Colonel Harold J. Rau of the Army Air Corps. “I want to put strong emphasis on the word ‘average,’ taking full consideration just how little combat training our pilots have before going on operational status.”

For example, if a pilot didn’t follow an exact set of steps after takeoff and powering up, he might ruin the engine and fall out of the sky. And it might be that 1st Lt. Charles Heitz was in the middle of turning two stiff gas switches, turning off drop tank switches, pressing the release button, changing the fuel mixture by conducting two different clumsy operations, increasing his RPMs, increasing manifold pressure, turning a switch for the gun heater which he might not even be able to see, and then flipping the combat switch when he missed a step.

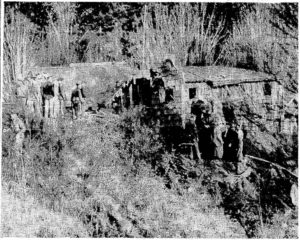

Photo courtesy: Seattle Public Library

And, at that point, the Thompsons heard the usually (relatively) quiet engines of the P-38 starting to make enough noise that they left their house. Heitz had flown the plane almost four miles before he crashed into the backyard at where Eastside becomes 22nd Avenue. The plane didn’t necessarily hit the house, but it did enough collateral damage to destroy a room on the outside of the house before the fire department put the fire out. And Mrs. Thompson avoided serious injury, only being hit in the head with a small piece of debris.

It isn’t that planes were falling out of the sky in those early days of World War II. But the story covering the Thompsons’ partially burnt house was folded into the story of another plane crashing north of Seattle literally minutes earlier. When the story jumped to the inside of the paper, it ran alongside another story of a bomber crashing in Idaho.