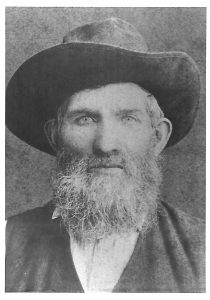

In 1849 as far as Easterners were concerned, the far western territories were a wilderness, and a foreign land beyond the United States of America. More than one mother and father said goodbye to a grown child who desired to go west knowing they may never see or hear from them again. Ignatius Colvin was one such youth. Since he was illiterate, no journals or letters exist of Colvin’s that would give us a window into his personality. But some reports, like Rev H. K. Hines 1893 sketch in “An Illustrated History of the State of Washington,” called him a “liberal-minded and public-spirited citizen.” He was also labeled a “Gruff old Codger” in Susan Erb’s essay titled, “Emma Ester Peck Rector Colvin.” His decedents think of him as a shrewd businessman.

The west called to young Ignatius Colvin in 1849, out of Boone County, Missouri. Like many 20-year-old men, he was up for an adventure and to find his fortune. He took a job driving a military commissary wagon carrying food, munitions and supplies from Fort Leavenworth to Fort Vancouver. This was probably an early expedition to the Fort, which had belonged to the Hudson Bay Company and had only begun transfer to the United States Army in May of that year. Colvin’s tenure with the army was short. By 1850 he continued his journey up to Cowlitz Landing where he hired a horse and guide and made his way to New Market, now known as Tumwater. There he worked hand hewing piles for Col. Simmons.

The west called to young Ignatius Colvin in 1849, out of Boone County, Missouri. Like many 20-year-old men, he was up for an adventure and to find his fortune. He took a job driving a military commissary wagon carrying food, munitions and supplies from Fort Leavenworth to Fort Vancouver. This was probably an early expedition to the Fort, which had belonged to the Hudson Bay Company and had only begun transfer to the United States Army in May of that year. Colvin’s tenure with the army was short. By 1850 he continued his journey up to Cowlitz Landing where he hired a horse and guide and made his way to New Market, now known as Tumwater. There he worked hand hewing piles for Col. Simmons.

Gold Fever and War

In 1851, lured by tales of gold, a company of 22 men plus crew set out on the ship Georgianna for Queen Charlotte Island. The ship arrived on the wrong side of the island. On November 18, it was caught in a storm that wrecked it. As the men struggled to shore, they were captured by Haida Native Americans. The Haida burned the ship, took most of the men’s clothes, and threatened to kill them. Though they were able to convince the Haida they were worth more alive than dead, the men still lived in a constant state of fear. Since they had no blankets the men slept in a pile for warmth. Lice were a problem.

After the men had spent 54 wintery days in captivity, a ransom and rescue were arranged by the United States Government. Colvin later made a second prospecting expedition to the island, which was also unsuccessful, but perhaps less disastrously so.

According to marriage records, in 1854 Ignatius married Ketty Socum, also known as Kirby Ann Socum. She was a Native American with whom Ignatius had one child in 1855 named Jeremiah Colvin. During this time period, Colvin applied for a donation land claim of 320 acres, which is the amount of land granted to an unmarried man. As a Native American, Ketty would not have qualified for the full 640 acres allotted to a married couple.

The Pacific Northwest Indian Wars broke out in 1855. Colvin joined the volunteer army under Captain C. Eaton. He is reported to be one of the men who brought back the dead from White River to Steilacoom including James McCallister. Some have wondered why Colvin enlisted when he was married to a Native American. One answer is that every able-bodied settler was expected to enlist. The other is that Colvin later received a Soldier Bounty of 160 acres from the United States. It is unclear if he was aware of the bounty, but if he were, it would have been a huge motivator for Colvin.

Ketty Socum disappeared from the family history and by 1860 the census shows only Colvin and five-year-old Jeremiah.

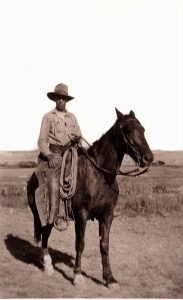

Working the Land

Colvin turned to the land for his fortune, and went about amassing a 3,000-acre farm. Many of the deeds he collected from buying up his neighbors’ property are still in possession of the Colvin family. Colvin didn’t just amass land for his farm but he also bought and sold for a profit, gaining his reputation as a businessman. Colvin employed Native Americans to help him build his ranch. In 1866 Colvin married Emma Peck Rector. A divorcee, she had been married to George Rector, and brought to the Colvin household her three sons, Jesse, Washington Irving and Franklin. The couple had four more children, Benjamin, Nellie, Sarah (Sadie) and Fred Ambrose.

Under the directorship of Colvin, the local Coal Bank School later became known as Colvin School. It was said that Colvin, who signed his name with an X, made it a priority that his children learn. All the children, including the children of any Native Americans who worked for him, attended. Colvin School existed for 80 years.

Family stories, told by Eldon Morrill, report that Ignatius used to disappear for months, sometimes years at a time leaving Emma to run the ranch. Wherever these expeditions were to, or for what purpose is unknown, but that he came home with money.

Complicated Relationships

The three Rector boys worked for other people and eventually settled in Hanaford Valley. This was probably because the boys found Colvin difficult. Despite this, when Washington Irving Rector and his wife Flora had their third child in 1894, they put their baby to bed in a box. When Colvin heard about this he went to Tenino and purchased a cradle, took it to the Hanaford Valley and said, “There, that’ll get that kid out of the box.”

There was an attempt at a divorce between Emma and Ignatius. According to the family, the Supreme Court in Washington heard the case and rejected the divorce noting that Emma had enabled Colvin to amass his ranch and she should therefore benefit from her hard work. Ben Colvin testified on Emma’s behalf. Another report is that Emma, in 1895, purchased the Lewis County property from Ignatius for a dollar which she transferred to her three sons as well as Ben Colvin.

Eventually Colvin, who smoked a pipe, developed mouth cancer. He and Emma went to San Francisco to seek treatment where he succumbed to his illness in February of 1898. He is buried in Forest Grove Cemetery in Tenino.

In his will, his cantankerous nature comes through. He left his wife one dollar, a sum he also left to his son Ben. His daughters received a life time residency on the ranch. His youngest, Fred, would inherit everything for himself and his decedents. It was stipulated that if any of the children gave any property to Emma or Ben they would forfeit their inheritance. But perhaps Ignatius felt that Emma and Ben had already received their due in the land that had cost Emma a dollar.

There is currently a Colvin Family exhibit at the Tenino Depot Museum until September 2021. You can also learn more about what is going on at the Colvin Ranch, which is currently run by the fourth generation, by visiting the Colvin Ranch website.