It may seem like a truly unprecedented time, and for the most part, that is accurate. However, humanity has a history of facing pandemics. The 1918-1919 Influenza pandemic circled the globe, and Thurston County was not spared. As different as things were a century ago, there are quite a few similarities between COVID-19 and the 1918-1919 Influenza H1N1, the last major pandemic that made its way through Thurston County.

Influenza H1N1—The “Spanish” Flu

Influenza H1N1—The “Spanish” Flu

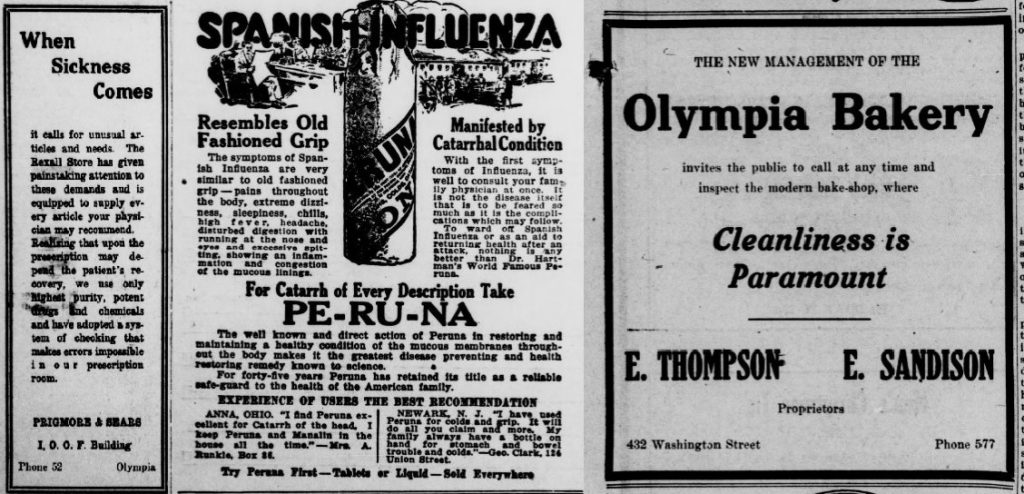

The 1918-1919 Influenza pandemic was commonly known as the “Spanish” flu. However, the disease did not start in Spain, nor did it have more devastating effects there. The pandemic occurred at the same time that most of Europe and the US were involved in World War I. To not appear weak to their enemies, countries involved in the war minimized news reports of the Influenza spread. Spain was neutral during the war, so news reports were not restricted, leading to the public perception that Spain was the epicenter of the pandemic. When Spain’s King Alfonso XIII died of the flu strain, the “Spanish” flu was solidified into the public lexicon.

Like COVID-19, Influenza H1N1 is a respiratory virus that spreads through droplet transmission and direct contact. Throughout Thurston County and the world, impacts from COVID-19 have very similar parallels to the 1918-1919 flu.

Empty Shelves

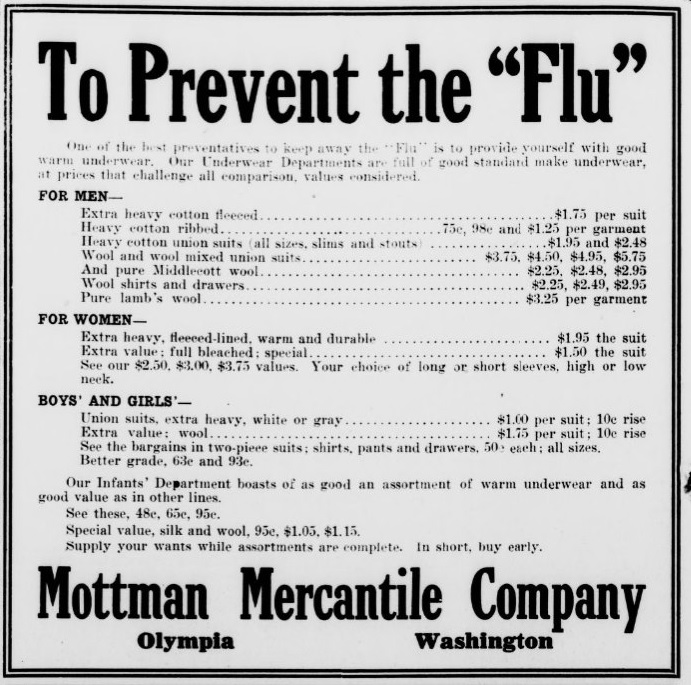

When news reports indicated that COVID-19 had reached Washington State, residents rushed to Costco and other retailers and began stocking up on hand sanitizer, soap, bleach, bottled water, and toilet paper, resulting in empty shelves and concerns about shortages. Area distillers like Sandstone Distillery and Shoebox Spirits responded to the increased demand for sanitizer, using their skills and materials to make recipes with the recommended alcohol content, providing the product to police and fire departments, health care personnel, and the public.

New shortages have surfaced, particularly in meat supplies and gardening seeds and equipment. Much of the meat processed for home consumption is done in large processing centers that have shut down after workers tested positive for COVID-19, resulting in temporarily decreased production. Seed shortages, much like cleaning supplies and toilet paper, have occurred from temporary increased customer demand. All shortages and disruptions are considered temporary fluctuations.

Thurston County residents faced their own shelf-shortages in 1918-1919. However, these shortages were not directly or indirectly a result of the flu. Rather, they were caused by wartime rationing. Sugar, wheat, and meat were the major shortages experienced by residents, and much like their modern-day counterparts, residents used creativity to minimize disruptions from the shortages.

Myrtle Boone was a district home demonstrator for Thurston County. Home Demonstration Clubs were supported by the USDA, state agriculture departments, and extension offices connected through state colleges and universities. During the war and concurrent pandemic, home demonstration clubs provided advice and information on topics like gardening and food preparation and preservation. In an era before Google and YouTube, these clubs and the information they provided in local papers and flyers were invaluable to families making do with shortages. Boone encouraged local homemakers of 1918 to substitute potatoes from Washington’s bumper potato crop in place of wheat flour for bread.

Grocery Delivery

Crowded aisleways at local grocery stores have encouraged residents to order their groceries online for curbside pickup or home delivery. Area grocers have also implemented a variety of methods to limit exposure of customers and employees, from limiting the number of patrons to floor markings indicating six-feet distance.

Curbside service and grocery delivery may seem like modern conveniences, but stores utilized this service in the early 1900s as well. Crabgrill’s Market, originally located on Fifth Avenue in downtown Olympia, advertised quality goods, including butter and canned food brought to their customers’ doors. Nearby Reder & Phillips reminded customers that they kept everything “clean and sanitary,” along with prompt delivery.

Closed Schools

On March 16, 2020, Thurston County Superintendents temporarily closed Olympia, North Thurston, Tumwater, Yelm, and Rainier schools, and after much deliberation Governor Inslee ordered all Washington schools closed through the remainder of the school year. Public gatherings have been prohibited, and services are reduced to essential.

In October 1918, Dr. H.W. Partlow, local physician, and county health officer ordered all schools to be closed, relaying an order from the state board of health. “The only way [the Influenza epidemic] can be stopped is to close every place where people congregate, the board of health stated. A second wave of the flu in early 1919 resulted in the closing of theaters, dances, and officials urged the public to stay home from all gatherings.

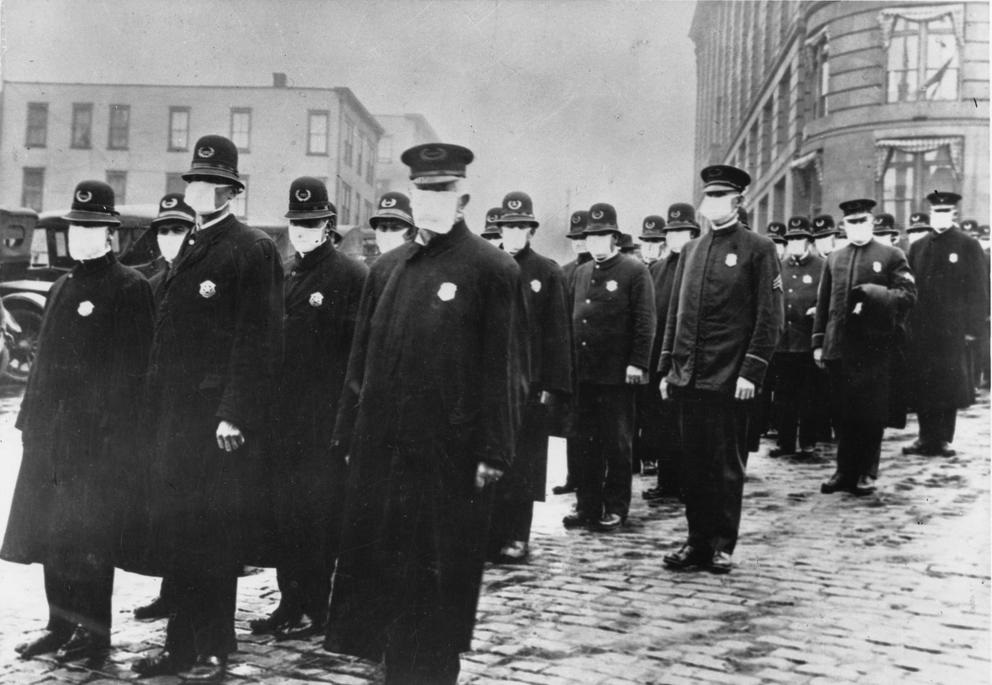

Masks

As more information has become available about the transmission and spread of COVID-19, public health officials have determined that, in addition to physical distancing and increased handwashing, face masks would be a useful tool to limit the spread of the infection, especially where physical distancing is difficult.

Current information indicates that cloth masks help limit the number of airborne droplets, which may reduce transmission of COVID-19 from asymptomatic people—not showing symptoms but still shedding virus particles—to unexposed individuals. Skilled sewers have taken up the call, selling cloth masks at low cost or giving them away free to friends, neighbors and members the community through online Facebook groups.

Masks were encouraged in 1918-1919 as well. The city of Seattle sent an emergency call to the Thurston County Red Cross chapter in October 1918 for 10,000 flu masks. Local workers met at the Temple of Justice on the capitol campus to sew 6-layer cotton masks. Current knowledge indicates that the masks likely limited and contained the spread of the disease from infected individuals, rather than directly protecting the mask wearers from inhaling the virus themselves.

In the modern age of commercial air, computers and the internet, 1918 may seem like a million years ago. However, hardly a century ago, Thurston county residents persevered through the global outbreak. If history reminds us of anything, it’s that the people of Thurston County will come through this pandemic as a stronger community, reinforced by the bonds forged during the pandemic, even while we physically distance.