For many of us, the Deschutes River is a peaceful place. We see it as a normally placid river, even when it courses through waterfalls.

But several times in the last century of so, the Deschutes River – and the economic power it represented – was the crux of legal and political struggles in our community.

But several times in the last century of so, the Deschutes River – and the economic power it represented – was the crux of legal and political struggles in our community.

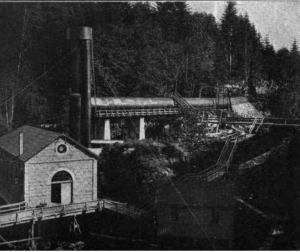

The Deschutes River was chosen as the center of Washington’s first non-native community because of the waterfalls where it enters the Puget Sound. Even though the era of water-powered industry was coming to a close in the mid-1800s, hydro-driven plants were still profitable enough to warrant waterfalls being desirable real estate.

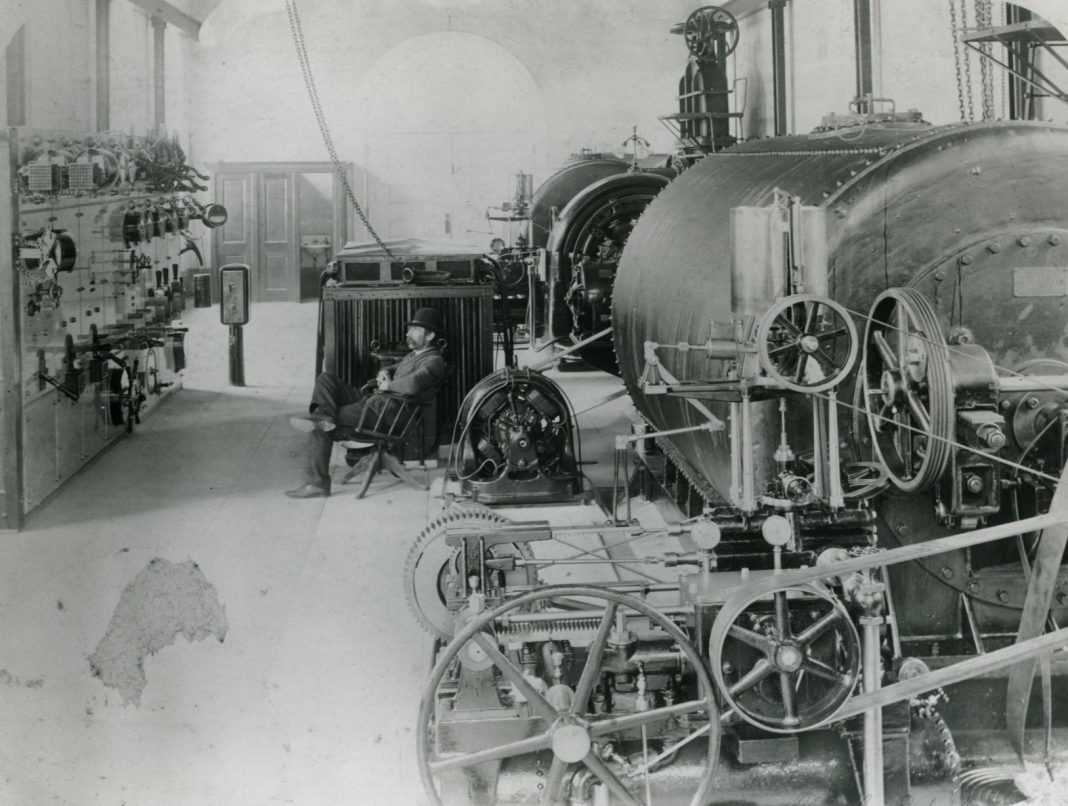

In 1905, the Olympia Brewing Company and Olympia Power and Light were locked in a court battle over who controlled flow through the lower portion of the river. Both companies were founded in the 1890s along the lower stretch of river and both had legal claim to some of the flow. Seeing that sharing was the most likely path forward, the Power and Light company – which supplied power to the city of Olympia – sought another path to ensuring its turbines would run during the dry summer months.

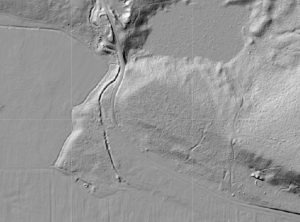

Moving from their fight with their beer-making neighbors, the power utility sought to dam a lake in the upper watershed. By creating a savings account of water at Lake Lawrence, Olympia Power and Light would be able to meter out flow throughout the summer. The utility wanted to dig a channel from the river to the lake, and with the help of a small dam, fill the lake in the winter months. Then, after enhancing the dam’s natural outlet, let out the lake water in the summer.

Unfortunately, that meant they would need to flood land already owned by someone else. So began the process in court to show that the company (because it supplied power to the city) had the right to condemn public property to build their canal and dam. After several years of court battles (and the old fight with the brewery, putting a monkey wrench in the gears), Olympia Power and Light was finally able to take over Lake Lawrence in 1912.

But just because Olympia Power and Light owned their own water storage lake and could at will make the dry river flow in summer, did not mean they controlled the entire river. In the late summer of 1915, Olympia’s lights and streetcars went without power for 15 hours because a shingle mill owner near Rainier dammed the river. After a quick investigation by city and utility officials, it turned out the Molberg Mill had built three dams, which in total, blocked up the river for more than 30 hours. The power utility took the mill owner to court, and after threatening to have him arrested, forced him to remove his dams.

Just as Olympia Power and Light was finishing up battles in the upper watershed, a new front opened up at the mouth of the Deschutes River for them and their old opponents, the Olympia Brewery owners.

City fathers in Olympia, which was a few miles downriver from the lower Deschutes Falls, hatched a plan to block off the mouth of the Deschutes as it entered Budd Inlet. The idea was to solve their perpetual problem of linking downtown Olympia with its Westside neighborhood. Several attempts at building bridges across the span proved to be ineffective. Another try at a bridge would not be needed, former Olympia’s Mayor and then-current state legislator P.H. Carolyn figured, if they physically connected downtown Olympia with the Westside with land.

It had only been a few years since much of what is now the eastside of Olympia’s downtown was created by Carolyn and his fellow city leaders by filling in the Moxlie Creek estuary. Damming the Deschutes at its mouth and creating a land bridge to the Westside, and coincidentally covering intermittent mudflats with freshwater, seemed to be a doable project.

But now the Olympia Brewing Company and the Olympia Power and Light Company had a joint mission. The beer makers feared being cut off from ocean transit, and the power company feared the impact a rising freshwater reservoir in front of their powerhouse would have on their hydro project. So, with the help of the city of Tumwater, they appealed to the state lands commissioner who had jurisdiction over intertidal land. The lands commissioner declared that Olympia could not cut Tumwater off from the sea without their consent and that since much of the land they planned to inundate was privately owned, they needed those landowners’ permission too.