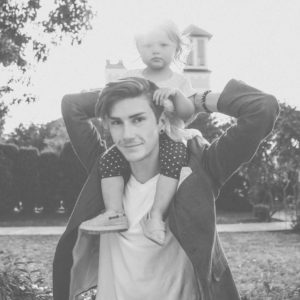

After two months spent hounding Arno Matz, a young photographer slowly gaining attention for his work documenting the homeless population, I was growing tired of unanswered calls. In search of a theme for my next article, Arno came highly recommended by a local store owner, if only I could reach the man. And then, finally, it happened – the silence contracted, the lights flickered, my skull buckled, I think the ceiling even shook because Arno Matz responded. Finally, it all made sense. Arno is a busy man – not to mention husband and father – humbled to hear anyone taking interest in his art.

Inviting me over to his Olympia apartment, Arno was quick with the hospitality, offering an amends of food and drink at the door. I gratefully accepted a quinoa stew, which I nursed while we conversed about art and healthy living. By the time we got around to discussing his photography, Arno was ushering his daughter from her plastic merry-go-round in the living room to her bed while speaking in German, his native tongue.

Inviting me over to his Olympia apartment, Arno was quick with the hospitality, offering an amends of food and drink at the door. I gratefully accepted a quinoa stew, which I nursed while we conversed about art and healthy living. By the time we got around to discussing his photography, Arno was ushering his daughter from her plastic merry-go-round in the living room to her bed while speaking in German, his native tongue.

Arno Matz grew up in Malente, a small rural town in picturesque northern Germany. His dad was a doctor, and his mom was a nurse in her husband’s office. They were married 14 years before Arno was conceived. When Arno was 12 years old, they emigrated to Mossy Rock. Upon arrival, he was pushed to grow up instantly, getting a job sorting x-rays in the doctor’s office.

Arno’s first foray into videography occurred later while creating snowboarding sponsor videos for his friends in high school. Extremely independent at a young age, he graduated high school a year early, eventually moving to Olympia to sell mobile phones for Smart Wireless. He was a natural salesman. Numerous snowboarding injuries, however, slowly initiated him into a habit of drug use. Painkillers were his entry pass into an abyss that was, he says, “not so much a speed bump or wall, but an imaginary line that is so easy to cross.”

Powered by Nietzschean ambition, Arno ultimately climbed to the position of district manager at Clear Wireless. When not analyzing sales metrics, Arno reveled in the vices of business culture: expensive cars, accessories and rampant promiscuity. Eventually feeling like, as he describes, “an animal with an unfathomable pit,” he left to become a personal banker for Wells Fargo, but the bank felt like an extension of the sales world.

Then one day a regular customer took Arno’s hand, pulled him aside and offered the pointed advice that he should live his dream before it was too late. Newly married with a one-year-old daughter, he quit banking, moving his family to Maui for six months. Yet the temptations remained, so a bout of hitchhiking and train hopping ensued. With the soul-searching settled, he worked next as a server at Applebee’s where he met a co-worker in need of video help for an upcoming event. The project taught Arno that he was capable of working on his own. And so he did.

During his daughter’s first birthday party, however, Arno had a seizure. To complicate matters, he was later diagnosed with radial palsy. When a pinched nerve led to a medical leave of absence, Arno left for Germany, building a portfolio with the use of a single hand. Feeling renewed, he returned to the United States ready to live his dream: working weddings and even shooting video for the Sasquatch Music Festival.

After four years chasing his dream, Arno currently makes a living from his freelance commercial work. Arno’s Sonder project, meanwhile, reflects his socially conscious side, too – exploring the hidden stories behind homelessness, a pursuit spurred, he says, by the premise that “every passerby has a life that is just as real and vivid as our own.”

Recognizing that we are all victims and perpetrators of our own identity, Arno notes that his subjects seem to perform for the camera – portraying a procession of faces ranging from guarded to hardened as each shutter clicks. Somewhere in the nebulous cracks between the person and the persona, between a smile and a scowl, Arno captures moments of vulnerability beyond our socially sanctioned veils, revealing people not as homeless and helpless, but hopeful and homeward bound.

Arno’s mother once recalled a time in second grade when he defended a handicap student being teased by a couple of older students. Arno supposedly stood up for the kid but received a thrashing in the process. Much like his younger self, he continues to serve people – albeit standing witness now with a camera lens.

Although the Sonder project has yet to receive wider recognition, Arno plans on persisting until the world takes notice, citing R. U. Darby’s oft-quoted self-help story (“Three Feet Short From Gold”) as inspiration. During the gold rush a group of miners prematurely abandoned a gold vein, believing that the gold vein had nothing more to offer. Frustrated, R. U. Darby and his group sold their land and equipment to the “junk” man on duty, who then wisely sought counsel. When the counsel confirmed that gold was still there (just three feet from where R. U. Darby had left off), the “junk” man struck it rich, on his own.

While Arno’s work promotes the value of all human relations, his life reminds us to push a little further where others fall just short. Do not stop three feet from gold. The vein is rich; the vein is here. Visit the New Caledonia Building to see Arno’s work displayed during Spring Arts Walk on April 28, 5:00 – 10:00 p.m. and April 29, 12:00 – 8:00 p.m.