The location of today’s Cedar Creek Correctional Center has a long history of rehabilitation. From its depression era origins through its youth camp years, it served young men in need of work, money, purpose and direction. Once the site of an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corp camp, just nine miles from Littlerock, it was transformed into the Cedar Creek Youth Forestry Camp. It facilitated treatment and guidance for boys who had found themselves in trouble with the law.

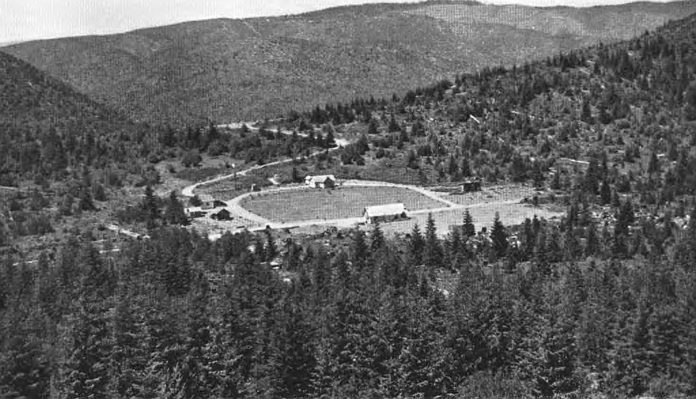

Until legislation was passed providing new rehabilitation facilities, there were only two in the state of Washington. The Washington State Training School in Chehalis, open since 1891, was the only place that housed boys. Found to be physically and philosophically inadequate for rehabilitating juveniles, the call for more options was met in the form of youth camps. It wasn’t a new idea. Forestry work camps for the CCC had been established as part of the 1933 New Deal Program. Single men, 18 to 25 years old, signed up for much sought after work. The crews built park shelters, ranger cabins and roads. Discontinued in 1942, the camp continued on as the Capitol Forest Nursery.

In 1951, the Washington State Legislature passed the Children and Youth Services Act. The act allowed the creation of forest camps as one of its means of providing education, custody, treatment and rehabilitation of boys in their teens. For that purpose, the Department of Institutions and the Department of Natural Resources converted the abandoned CCC camp at the nursery.

July 7, 1952, the camp facilities opened, occupying buildings left behind by the CCC. Population started out at maximum capacity with 25 boys. Some were transfers from the WSTS, and some arrived straight from processing at Tacoma’s Cascadia Juvenile Reception-Diagnostic Center. It wasn’t long before success in the program called for increasing capacity. The original site was enlarged in 1955, increasing capacity from 25 to 32. A new building, called Cedar Creek Youth Camp, was constructed in 1959. It could house 45. Just one-half mile apart, both fully functional sites were used. A school program was added, and in 1961, boys were bussed over to Maple Lane School for classes. New buildings in 1963 at Capitol Forest Youth Camp made room for 90 kids total. Then, in 1966, both were covered under the name Cedar Creek Youth Camp. Barracks at the old Capitol Forest site were renamed Alpine, and the old Cedar Creek barracks renamed Timberline.

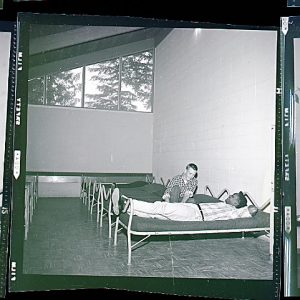

The state’s bureau of juvenile rehabilitation emphasized that the camps were not workcamps. Their 1962 report describes them as, “small, specialized, self-contained rehabilitation units” that treated a carefully selected clientele of 16- to 18-year-old boys. Average stay was about seven months, many being admitted for misdemeanor crimes. An intake board, led by the assistant superintendent and camp counselors, decided whether a boy would live in Alpine to work and obtain schooling or stay in Timberline to work on DNR crews learning positive work habits and attitudes. They worked on the old CCC roads and culverts, performing seed extraction and tree planting like the CCC did. They learned equipment maintenance, fire suppression, built structures, drove tractors and maintained irrigation systems. Similar to the CCC, they didn’t keep all of their pay. Every dollar was split three ways for their upkeep, for savings and for spending. Off work time included morning and evening flag muster and barracks inspections. Leave time to go home could be earned after three months. Phone calls and letter writing were allowed, and families were invited for Christmas dinner.

Residents from the south county area worked in the facility. The secretary was from Littlerock and the cook from Rochester. Thurston County Historic Commission member Ken Balsley was living in Tenino when he worked there. “It wasn’t a prison setting,” says Balsley, who was a day counselor at Cedar Creek for five years, “but it did have an institutional feel. I was just out of the military, and there was not a big difference between that and the way the camp was run. The kids never went without supervision. I was working with the kids in Alpine barracks during the day. I played a lot of ping-pong and pool to help build rapport. I took attendance on an hourly basis and took the kids to their lunch every day.” Counselors of different levels worked on site and did case management, staying in contact with others who worked with the boys on their caseload.

“The whole purpose was to get them back to feeling confident about themselves,” continues Balsley. Things changed as time went on though. “When we really began to feel the difference was when drugs became a problem. That was different from kids that got in trouble for stealing. The attitude changed depending on the kids that were there.”

Culture was going through changes and so was the law. The Juvenile Justice Act that was implemented in 1978 influenced the populations of juvenile facilities, diverting them away from correctional institutionalization and toward community-based programs. In 1979, Cedar Creek became an adult facility. Today, it is still a place of local employment and in operation as a correctional facility.