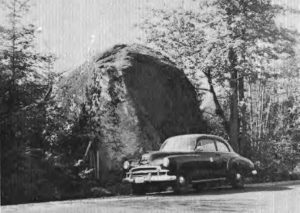

During a scenic drive through Thurston County, you can see evidence of a past ice age. A massive boulder near Lake Lawrence and the City of Rainier marks the path of a glacier. Occasionally, large boulders catch our attention around the county. Some are the size of a small car, and we know there’s something unique about them because clearly, they are too big to have been a landscaping afterthought. And they did, in fact, come from somewhere else. It was from a monumental event, the last ice age.

These extremely large boulders, officially called erratics, are actually debris that were dribbled from the bottom of a passing glacier. The United States Geological Survey defines them as, “A rock of unspecified shape and size, transported a significant distance from its origin by a glacier or iceberg and deposited by melting of the ice.” Its name derives from the same root as the more familiar word, errant, meaning straying or traveling. The boulder out near the Lake Lawrence community is an impressive, 15-foot-tall erratic. An explanation of how it got to 153rd Avenue outside of the Rainier community requires a narrative about the origin of rocks in the Cascade Mountain Range.

These extremely large boulders, officially called erratics, are actually debris that were dribbled from the bottom of a passing glacier. The United States Geological Survey defines them as, “A rock of unspecified shape and size, transported a significant distance from its origin by a glacier or iceberg and deposited by melting of the ice.” Its name derives from the same root as the more familiar word, errant, meaning straying or traveling. The boulder out near the Lake Lawrence community is an impressive, 15-foot-tall erratic. An explanation of how it got to 153rd Avenue outside of the Rainier community requires a narrative about the origin of rocks in the Cascade Mountain Range.

Rocks of any size originate in three ways. They form out of metamorphic changes due to heat and pressure, form out of cooling magma or form out of sedimentary compaction. The Lake Lawrence rock was formed and cooled in magma chambers below the earth’s surface, categorizing it as an intrusive, igneous rock. Granites, including granodiorites such as this rock, are igneous rocks and formed in regions like ours because of our location on the planet. Thurston County, and the surrounding Western Washington area, is on the perimeter of the Pacific and North American tectonic plates where there is an induction zone of the Juan De Fuca plate pushing beneath the North America, creating mountains. After erosion occurred and eruptions dislodged material, this erratic surfaced. Its geochemistry can be traced to Mount Rainier, and its path down into the valley can be mapped.

Photo credit: Rebecca Sanchez

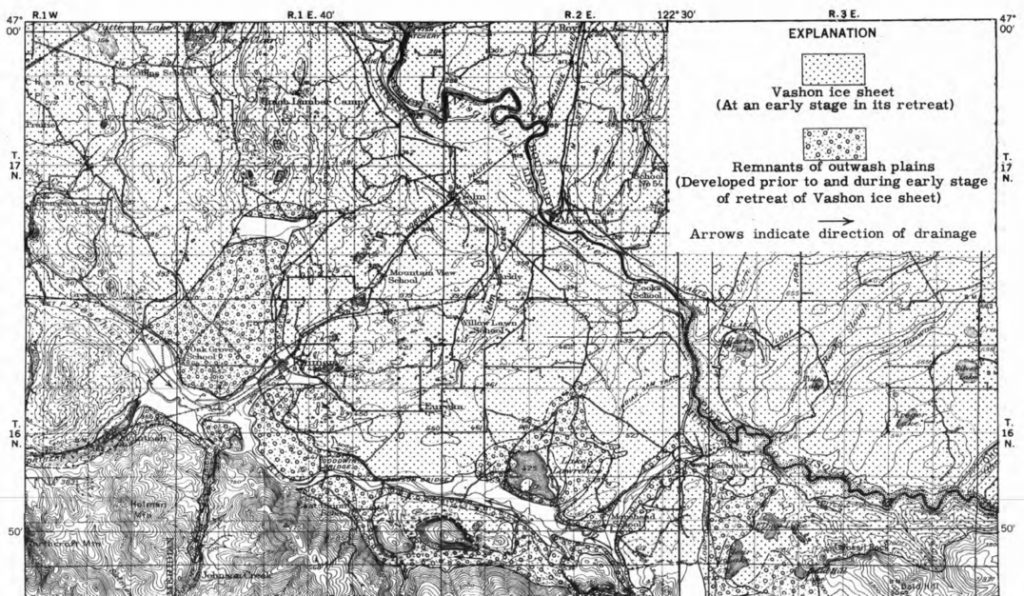

The Cordilleran ice sheet spread down from the Canadian north and covered the lowland parts of British Columbia and Western Washington. The Puget Lobe of this ice sheet covered the Puget Sound area, including Thurston County. About 16,900 years ago, the ice sheet was 700-feet high in its southernmost reaches covering Olympia. Despite its heights of 3,000 feet near Seattle, the ice still wasn’t high enough to cover the Cascades nor the Olympic Mountains. The lobe dammed up against the lower foothills, preventing Mount Rainier’s glacial ice from descending any further. Eventually, when the lobe retreated, ice and water could move down the mountain into the lowlands. Glaciers, holding whatever rocks that the snow and compacting ice had trapped inside, were then able to melt and move. Imagine the great movement, the great heights of an ice flow and the 15-foot-tall erratic scraping off the bottom.

“Realize that something had to transport it to this location,” notes Michelle Harris, associate professor of geosciences at Centralia College. “It’s out of place and doesn’t belong. The only thing that could have brought it here is a large amount of ice. Its presence allows geologists to reconstruct how the last ice age helped to shape our region.”

When you notice one of these very large boulders, it is likely an erratic moved by ice. Smaller boulders that were moved by water are the smooth, round type we see in rivers and streams. Large erratics sitting out on open ground can be seen easily. However, drivers may actually miss the boulder on 153rd Avenue. Western Washington’s forests tower over large erratics. Even a Google Earth search will likely leave this particular boulder hidden from view. Coincidentally, for scientists studying their origins and the paths they took, there’s hope for making that identification easier. “New lidar technology has provided geologists with another tool,” explains Harris, “to help decipher the glacial history of the Pacific Northwest. We are able to see the region in a whole new way. This technology has brought new insights and understanding to things that we thought we had already figured out.”

Geological curiosities and enormous boulders have long fascinated the human race’s curiosity. We wonder how they got there. The erratics we see in Thurston County hold clues to that story. “I asked the boulders I met, whence they came and whither they were going,” mused naturalist and explorer John Muir. He might have heard from this boulder that it came from deep beneath the Cascade Range, had rested near Lake Lawrence and will not be going anywhere further.

The rock is just under one mile east of Dylan’s Corner Market on 153rd Avenue on the south side of the road. If you pass Lindsay Avenue and the volunteer fire station, you’ve missed it. The location is not safe to visit on foot. There are no paths or space to stand, but a westbound drive past gives a good view.