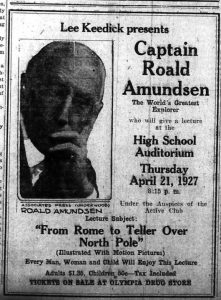

On April 21, 1927 people crowded into Olympia High School’s auditorium to listen to a Norwegian explorer give a talk. Despite a faulty motion picture projection screen, the audience eagerly listened to the man describe his latest polar adventure: crossing the North Pole in an airship. His name was Captain Roald Amundsen.

Amundsen was born in 1872 in Norway (then ruled by Sweden), the youngest son of a wealthy shipowner. Although his mother wanted him to become a doctor, Amundsen was fascinated by the exploration of the Arctic. Less of a scientist than an explorer, most of his expeditions were focused on the goal of achieving “firsts.” Although he was sometimes supported by the Norwegian government, his travels were largely privately funded and he had continuous money problems. Lecture tours, like his visit to Olympia, helped pay off his debts.

Amundsen was born in 1872 in Norway (then ruled by Sweden), the youngest son of a wealthy shipowner. Although his mother wanted him to become a doctor, Amundsen was fascinated by the exploration of the Arctic. Less of a scientist than an explorer, most of his expeditions were focused on the goal of achieving “firsts.” Although he was sometimes supported by the Norwegian government, his travels were largely privately funded and he had continuous money problems. Lecture tours, like his visit to Olympia, helped pay off his debts.

Even before the historic 1926 flight, Amundsen had collected an impressive list of firsts. He and his crew were the first to cross the Canada’s Northwest Passage by ship (1903-1905). A route linking the Atlantic and Pacific had been sought by western explorers for centuries, but although this Arctic passage had been discovered earlier it had not been crossed. During this expedition, Amundsen stayed with the Netsilik Inuit (an indigenous group) and learned many polar survival skills.

These skills would help Amundsen achieve his greatest claim to fame: being the first to reach the South Pole in Antarctica in 1911. His claim was heavily disputed at the time. A British expedition led by Captain Robert Scott arrived two weeks later and perished on the return trip.

Amundsen was not ready to retire. Fascinated by the possibility of exploring the Arctic by air, he was the first person in Norway to receive a pilot’s license. After his first attempt to cross the Arctic by airplane failed, he partnered with American millionaire explorer Lincoln Ellsworth and the Italian government to cross the Arctic by airship in 1926. He was reluctant to accept aid from the Italians (Mussolini’s fascist party had taken over the country in 1922), but needed the funding and their airship. The airship was captained by its designer, Major Umberto Nobile.

This expedition, known as the Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile Transpolar Flight, was what Amundsen shared with his Olympia audience through slides and motion picture footage. The Italian crew (who had never seen snow before the trip) flew the airship Norge from Rome to Svalbard (an archipelago halfway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole) where Amundsen joined them.

They then set off across the Arctic Ocean, tossing out flags above the North Pole before making their way to Teller, Alaska. The journey was a difficult one. The Norge was basically a framed hydrogen filled rubber cloth balloon with a gondola attached and was difficult to maneuver. It had the advantage of not crashing if the engine should fail, but the 13-member crew was kept busy handling ice build-up on the ship and checking for gas leaks.

Fresh from his accomplishment, Amundsen stopped in Seattle before going on a lecture tour of the United States in spring 1927. Amundsen had a special connection to Washington that would not have been lost on Olympians. His ships had sometimes landed in Seattle when coming down from Alaska. Perhaps some Olympians had gone to see them.

Amundsen’s talk in Olympia was sponsored by the Active Club (founded in 1922). Now called the Active 20-30 International, the organization currently focuses on helping children. The Olympia branch no longer exists.

A Morning Olympian reporter, identified only as J. B. L., visited with Amundsen in the lobby of the Hotel Olympian (built in 1918 across from Sylvester Park) shortly before he left to give his speech. “When I was 15 years old,” Amundsen, who spoke fluent English, said, “I knew what I was going to do when I grew up and I worked and studied and planned for that end. It was the tales of the old British explorers that captured my imagination and I knew then that my ultimate work would take me to the polar regions.”

“Now,” the reporter wrote, “he says, he sometimes wonders, with the advance of age, whether the time will come when he will wish that he had chosen the fireside sort of life, a time when he will feel alone. But there is so much of accomplishment, of worth-while memory lodged in his virile body that his life seems indisputably and permanently tied up with adventure, exploration and the wonders of the distant places of the world. So far, he says, it has been. Now, though, he points to the fact that his chief objective has been grained and suggests that it is possible no new interests will come to fill out his life. One doubts that, though, with Amundsen.”

After visiting Olympia, Amundsen went to Canada before continuing on to Japan and Russia before returning home to Norway. But the reporter’s words proved prescient. A year after his visit to Olympia, Amundsen’s plane was lost on an international rescue attempt to save Nobile and his crew, whose airship had gone down in the Arctic. People followed the news closely for days as hopes of finding him and his group faded. Although Nobile and his crew were eventually rescued, Amundsen’s body was never recovered.

News of Amundsen’s death must have shocked those who had seen him in Olympia. As J. B. L. noted in April 1927, “most members of the audience…found listening to this man both a privilege, a valued experience and a trip into the realm of high adventure.” Indeed, Amundsen’s achievements are still remembered today, almost a century later.