On July 6, 1870, a group of seven women cast their ballots in Grand Mound. A rider quickly sent the news “They’re voting!” to nearby Littlerock, where eight more women cast their ballots. Why all this excitement? This was the first time women voted in a general election in Washington Territory, and their legal right to was on uncertain ground.

In 1870, nearly all American women could not vote. The suffrage movement, born out of the Seneca Falls Convention (1848), was fighting an uphill battle. After the Civil War, suffragists saw an opportunity for action with the passing of the 14th and 15th amendments, which were in theory supposed to secure equal protection under the law and voting rights to all male citizens. Suffragists argued that these amendments gave women the right to vote as well.

In 1870, nearly all American women could not vote. The suffrage movement, born out of the Seneca Falls Convention (1848), was fighting an uphill battle. After the Civil War, suffragists saw an opportunity for action with the passing of the 14th and 15th amendments, which were in theory supposed to secure equal protection under the law and voting rights to all male citizens. Suffragists argued that these amendments gave women the right to vote as well.

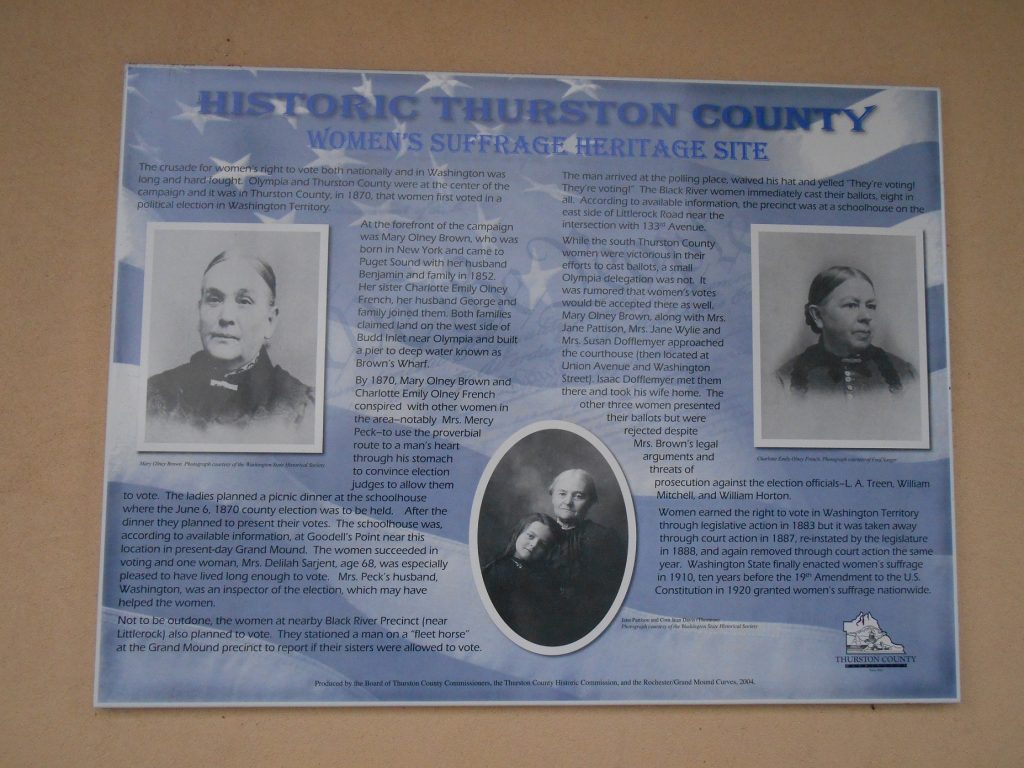

In 1867, the territorial legislature passed a bill that allowed all white American citizens over 21 years old to vote. Sponsor Edward Eldridge of Whatcom County, a suffragist, claimed to have left the word “male” out on purpose. Sisters and suffragists Mary Olney Brown (1821-1886) and Charlotte Emily Olney French (1828-1897) decided to test the new law.

In 1869, Mary attempted to vote in King County’s White River precinct. Accompanied by her husband, daughter and son-in-law, Mary defended her right to vote before election officials, arguing that both the 14th amendment and territorial law ensured her rights. However, her ballot and her daughter’s were rejected on the grounds that the courts had not instructed election officials to receive women’s ballots and doing so could jeopardize the legality of all ballots cast in the precinct.

Throughout the year, Mary wrote a series of newspaper articles about suffrage and personal letters to prominent women encouraging them to go to the polls. Mary described what happened next in Woman Suffrage (1886):

“My sister, Charlotte Olney French, living in Grand Mound precinct, some twenty-five miles from Olympia, began talking the matter up; and, being a woman of energy and influence, she soon had the whole neighborhood interested. With the assistance of an old lady, Mrs. [Mercy Mary] Peck, she planned a regular campaign [Mercy’s husband Washington was one of the precinct’s election inspectors]. By the programme the women were to get up a picnic dinner at the school-house where the election was to be held, and directly after, while the officers of election were in good humor (wives will understand the philosophy of this), they were to present their votes. My sister, being a good talker and well informed on all the constitutional, judicial and social phases of the question as well as a good judge of human nature, was able to meet and parry every objection, and give information where needed, so that by the time dinner was over, the judges, as well as everybody else, were in the best of spirits. When the voting was resumed, the women (my sister being the first) handed in their ballots as if they had always been accustomed to voting, and everything passed off pleasantly. One lady, Mrs. [Delia] Sargent, seventy-two years old, said she thanked the Lord that He had let her live until she could vote. She had often prayed to see the day, and now she was proud to cast her first ballot.

“It had been talked of for some days before the election in the adjoining precinct—Black River [later the post office was renamed Littlerock]—that Mrs. French was organizing a party of women to attend the election in Grand Mound precinct; but they were not sure the judges would let them vote. ‘If they do,’ said they, ‘if the Grand Mound women vote, the Black River women shall!’ So they stationed a man on a fleet horse, at the Grand Mound polls, with instructions to start as soon as the women began to vote, and ride with all haste back to their precinct and let them know. The moment the man rode in sight of the school-house he swung his hat, and screeched at the top of his voice, ‘They’re voting! They’re voting!’ The teams were all ready in anticipation of the news, and were instantly flying in every direction, and soon the women were ushered into the school-house, their choice of tickets furnished them, and all allowed to vote as ‘American citizens.’”

Mary and a group of women attempted to vote in Olympia, but were rejected at the polls.

In 1871 the territorial legislature voted to not give women the vote until Congress approved it nationally. However in 1877 taxpaying women won the right to vote in school elections. The legislature passed women’s suffrage laws in 1887 and 1888, but both were overturned by the Territorial Supreme Court. Washington State women finally won the vote in 1910. Washington was the fifth state to enact suffrage legislation, 10 years before the rest of the nation.

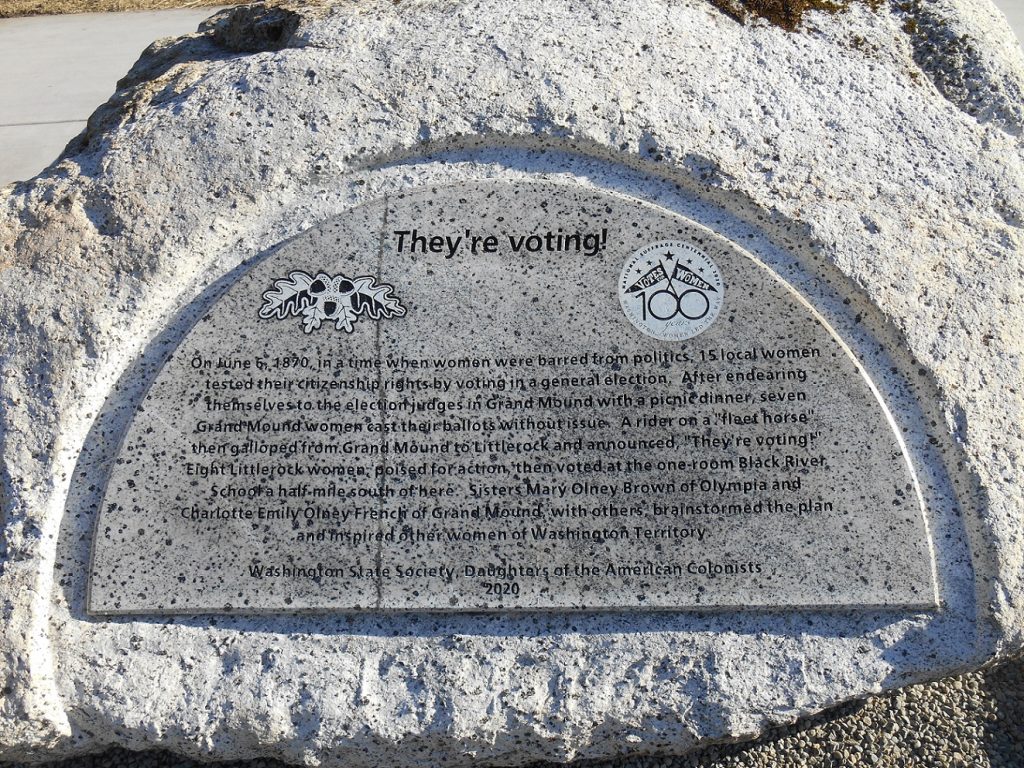

There has been much work to commemorate these groundbreaking 1870 events. The Thurston County Historic Commission has an interpretive panel near the Department of Licensing Building in Grand Mound (19810 Old Hwy 99 SW Unit 3, Rochester). In early fall 2020, the Washington State Society of the Daughters of the American Colonists dedicated a marker outside Littlerock Elementary School (12710 Littlerock Rd SW, Olympia).

Mary and Charlotte remained active suffragists. Mary served as the first president of the Washington Territorial Woman Suffrage Association and later the national association’s Vice President for Washington. She pushed for black male voters and activists to help black women also obtain the vote; and her writing on this topic was later published by Frederick Douglass. Unfortunately, neither sister lived to see suffrage victory. Still, the daring act of the women who voted in Grand Mound and Littlerock that summer day in 1870 helped pave the way for all women to vote in Washington.