Anthony Brock didn’t feel like he was part of the Olympia community he spent his childhood in. Even though he grew up off of Wilson Street in the Northeast neighborhood and attended Roosevelt Elementary School, Brock says, “As a student, I wasn’t really connected to Roosevelt. I felt like there was this whole world that operated there – and then there was my family. There was only one other person of color there, an African American male – and we’re still best friends to this day.”

![]() Brock tells this story while sitting at the San Francisco Street Bakery, a stone’s throw away from Roosevelt, where he just spent the past year working as the assistant principal. In addition, his time was divided this year by filling another very important role for the Olympia School District (OSD) as the staff and diversity coordinator.

Brock tells this story while sitting at the San Francisco Street Bakery, a stone’s throw away from Roosevelt, where he just spent the past year working as the assistant principal. In addition, his time was divided this year by filling another very important role for the Olympia School District (OSD) as the staff and diversity coordinator.

“Growing up, I wouldn’t have classified myself as a student leader,” he reflects, “because I felt disconnected. I struggled in school. Really, really struggled.”

He recalls a pivotal event as a sophomore when he was failing biology. In an attempt to remedy his grade, he missed the bus, which meant he’d have to wait for a ride. Unable to “just sit and wait,” he ended up wandering into an Associated Student Body leadership meeting with the school’s principal.

Brock was quiet the whole meeting, until the principal asked him, “What about you, what’s your name?”

Brock shared and he said, “Here’s my problem: every teacher, every administrator, counselor in this school is white. But the people who mop the floor, the people who cut the grass, the people who serve lunches – they look like me. And so it’s real clear to me that if you want to be a person of power, you’ve got to be white. That’s our problem, not parking spaces or school lunches.”

That moment in high school changed things for Brock, and he has been having this same conversation and more ever since.

When Passion Turns into a Career

Brock has attended numerous seminars, conferences, and working groups – his first one with prominent leaders from organizations like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference in attendance. Nationwide, only 10 students were selected to participate, and Brock remembers that the jam-packed seminar seemed to drag on. When it was time for him and the other students to present, people snapped to attention. “We didn’t say anything transformative or radical,” he says, and Brock struggled to understand the sudden interest.

So his mentors explained, “Anthony, you don’t get it. You’re next. It’s your turn next to lead. So we all care about what you have to say.”

“Dang,” says Brock. “That was powerful and profound to me, so I was like, I’d better figure out something.”

Brock had a mentor ask him if he was applying to colleges, and his response was, “College isn’t for a kid like me. My family didn’t fit in here in K-12 education, my parents didn’t go to college, my grandfather dropped out in sixth grade because they told him not to speak Spanish. I’ve got to get a job and make money for my family. Do you have thousands of dollars sitting around for me to go to college?”

On Going to College and The Martinez Fellowship

Brock did go – three times in fact. He graduated twice from the University of Washington (UW) and holds a Masters in Educational Leadership from Columbia University. “There are very few people of color who attend Ivy League institutions,” he says, “and even when I was on campus there, there were some folks who struggled to learn from and work with the few people of color present. It is important to me that students know people of color are present in some of the most ‘elite’ institutions in the world.”

In his time at UW, Brock had his first encounter with an educator of color. “Dr. James Banks was phenomenal – the grandfather of multicultural education,” Brock says. “I almost cried on the very first day of class. I remember walking in and seeing him and thinking, ‘Wow, he could be my grandfather. He looks like someone who could be in my family.’ It changed my world!”

It was also at UW that he discovered a flyer for the Martinez Fellowship Program. “Support Teachers of Color Throughout the State of WA” it said. “This was for me,” he says. “I felt like that’s why I was supposed to go to UW.”

Brock got accepted into the Fellowship, and on his first day, he met Holli Martinez, program founder and Edgar Martinez’s wife, where she warmly said, “Welcome to the family.”

“That’s what this was all about for me!” Brock exclaims, and recalls feeling like, “Where have y’all been my whole life?” When he looked around at the other Ambassadors in the program, he saw 10-12 other educators of color, and at the summer retreat, he saw 50 more. Nowadays, the ranks of the Ambassadors in the program number into the hundreds.

“I have spent my whole life looking for what I thought was impossible,” Brock says, “and now I have an entire community. I wouldn’t be in education if it wasn’t for this Fellowship.”

Affecting Change at Home

According to Brock, every school in this State wants to diversify their teaching force. “In the State of Washington, roughly 90 percent of our teachers are white. But our kids don’t represent that,” he says. He shares that teachers of color have a higher rate of burn-out and through the support of the Martinez Fellowship, he’s finding ways to support them as an administrator. He’s also using the Fellowship network to recruit educators of color for OSD. Brock doesn’t want today’s kids to grow up feeling like he did throughout his K-12 education.

“Every day I wake up with a laser-focus,” he says, “to embed equity and education into everything I do.” In practice, this looks like being the advisor for Olympia High School’s African American Alliance Club, or writing grants and securing funds from Teaching Tolerance. For the past two years, Brock and a group of community organizers have used those funds toward conferences they organized called “Stay Woke!” They’re student-led conferences for youth of color, where this past year guest speakers such as the legendary, Dolores Huerta and young activist, Bria Smith gave keynote speeches inspiring 250 students of color attending from 10 local high schools.

Part of the work that Anthony Brock is doing now looks a lot like the passing of a torch. Just as his mentors had shown him, Brock recognizes that today’s youth of color need a platform and a little framework to lead – and Brock is here for it.

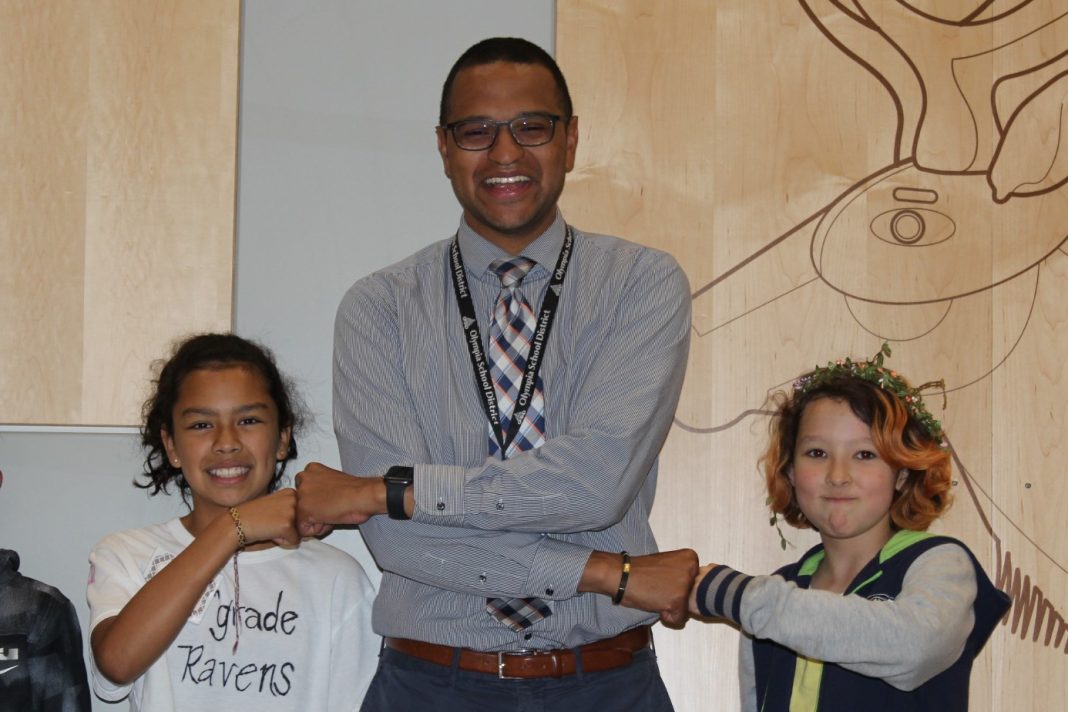

“This past year has been about improvement for me. What I hope I’ve done at Roosevelt is make it for kids who are very much like myself, who grew up in this area but don’t necessarily feel connected to school and to try and get them connected in some way. It’s so much about relationships, to truly get to know kids.”

Anthony Brock has accepted a position as the incoming principal for McLane Elementary School. There, he will continue to fulfill his life’s work in showing students of color that they can be anything they set their minds to.

This article is part of an ongoing series highlighting the work and contributions of public employees. It’s produced with support from WSECU.