On Tuesday, April 29, 1965, Thurston County was hit by the 6.5 Puget Sound Earthquake. With an epicenter near Des Moines, Washington, it was felt throughout the Pacific Northwest. While local damage was comparatively light compared to the 1949 Olympia Earthquake, it still required millions of dollars and years to repair.

Historic Earthquake in Thurston County

At 8:29 a.m. two brothers, 8-year-old Drew Crooks (my dad) and his 11-year-old brother Marc (my uncle) were walking to Madison Elementary School (now home to New Bridge Community Church). Passing by Saint Michael’s Catholic Church, they just made it by a house when the ground began to visibly roll. These Rayleigh waves or ground rolls reminded Marc of waves on a bay or lake. He remembered his earthquake (and nuclear) drills from school and what he learned from Cub Scouts and kept his brother and himself away from the swaying telephone wires. Drew remembers being too young to realize what was going on. Excited, they continued to school. Classes were still held.

The shaking sent many in the community running outside. The Chamber of Commerce, enjoying a breakfast meeting at the Jacaranda, scattered, though only a few glasses were broken in the building. Across town, fill dirt liquefied, collapsing Deschutes Parkway into Capitol Lake.

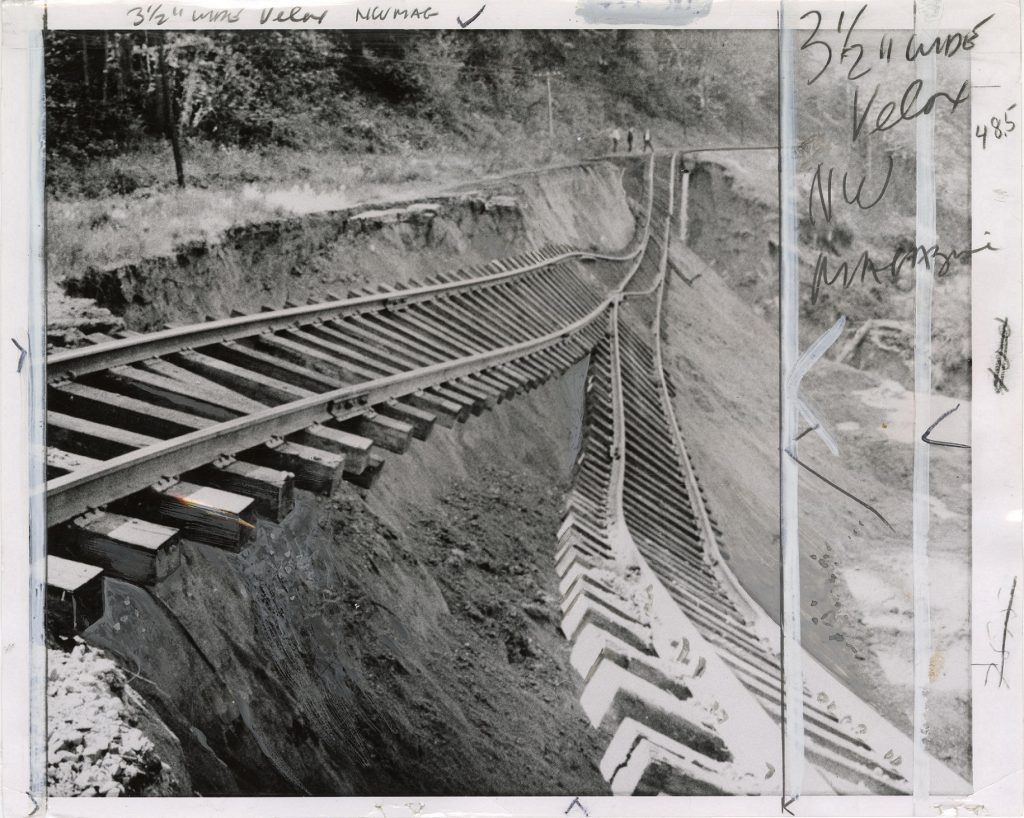

Tons of hillside across from Wildwood Center tumbled downhill, covering a railroad spur line and leaving 50 yards of the Union Pacific Line dangling. The slide also severed a City of Tumwater sewer line, spilling raw sewage into Capitol Lake.

Chimneys toppled and ceiling plaster rained down. Workers at Capital Motor Boat Mart might have thought their windows were safe after riding out the 1949 earthquake but they were shattered like so many others.

Luckily, few people were hurt. “The [mail sorting] room started to shake,” Olympia mail carrier Jenner Hames told reporters, “and I ran for the door jam—but I didn’t make it.” He was hit by falling fluorescent lights and rushed to St. Peter Hospital. Two other workers were also hurt.

Olympia High School chemistry teacher Herbert Challen was struck by falling glass from the second story library, leaving him with a broken shoulder and badly cut up, as he rushed outside to check it others were injured.

Only one local death could be contributed to the earthquake. Zenola Lorenz, a State Department of Licensing employee, passed away from a heart attack in her Hotel Olympian apartment.

1965 Washington Earthquake Aftermath

Moments after the shaking stopped, sirens rang out as the fire department moved their trucks outside. In the end they only had to respond to two minor house fires.

People quickly began cleaning up. While power remained on throughout most the area, Olympia City Hall had to use a generator until theirs could be restored later in the morning. At the Olympia Post Office, mail was moved out of the damaged sorting room. Building and Grounds workers salvaged 20 Japanese cherry trees along Deschutes Parkway, climbing down holes as much as 25 feet deep. Only four trees were lost.

Tumwater’s sewage spill proved a tricker problem. Chlorine was dumped into Capitol Lake as the city waited for new pipe to arrive. Officials assured a skeptical public that the chlorine would not kill the millions of salmon fry in the lake. Meanwhile the lake was closed to swimmers.

Applications for repair permits flooded Olympia City Hall. Damaged chimneys were the most common problem and the city waived permit fees for chimney repairs under $20. Many took up the offer.

Deschutes Parkway had to be completely rebuilt. Weather delayed paving, but workers finally removed barriers at noon on December 22, 1965, opening the road. There was no celebration. Salvaged cherry trees had to wait in the Capitol Conservatory for replanting in the spring.

Repairing the Washington State Capitol

The Capitol campus suffered significant damage. The quake sent books tumbling at the Washington State Law Library in the Temple of Justice and opened a 30-foot-long crack. The Highway-Licenses Building was evacuated. Elevators jammed and thousands of papers on the seventh floors, were scattered, upsetting the engineers planning the freeway. File cabinets tipped over, spilling folders.

Falling plaster and shattering skylights sent legislators and state workers fleeing from the Capitol Building. The rotunda’s five-ton chandelier was left swinging like a pendulum for 30 minutes. Repaired after the 1949 earthquake, the cupola weathered the 1965 disaster well. While harm to plaster walls and columns was mostly cosmetic, the worst damage was to the support structure between the inner and outer domes. Inspectors closed off the rotunda.

The dome was encased in a cocoon of scaffolding as work began and the inner dome was stiffened with a 60-foot high and foot-thick layer of spray-on “shotcrete” on the sixth and seventh floors. Eleven of 22 exterior windows were covered with concrete panels, darkening the rotunda. Thirty-two decorative outside columns also had to be removed to make way for this fortified wall.

Seismic work on the Capitol continued into the 1970s when sheer concrete walls were added behind existing walls to increase lateral resistance in future quakes. Skylights were covered in the legislative chambers and new built-up roofing installed on the fifth-floor decks.

The total cost of seismic upgrades and quake repairs to the Legislative Building totaled $9.6 million, more than the original cost of the building. But these changes would help the building weather the 2001 Nisqually Earthquake. The 1965 earthquake proved a wake-up call to many in the Pacific Northwest about the importance of earthquake safety. The 2001 Nisqually Earthquake did the same. And now…wait, why is the room moving?