In 1901 Thurston County Commissioner and pioneer Tom Prather sought to forestall Halloween theft in Olympia by removing his gate and storing it in his house overnight. In the morning he put the gate back up. The next evening, while watching three youngsters run off with his gate to his surprise, he realized that he had been a day off in calculating the holiday. Fortunately, Prather found the gate nearby the next morning.

![]() Halloween in turn of the century Olympia was in the middle of a transformation from a night of spooky mischief to a holiday celebrated by trick-or-treating and holiday parties.

Halloween in turn of the century Olympia was in the middle of a transformation from a night of spooky mischief to a holiday celebrated by trick-or-treating and holiday parties.

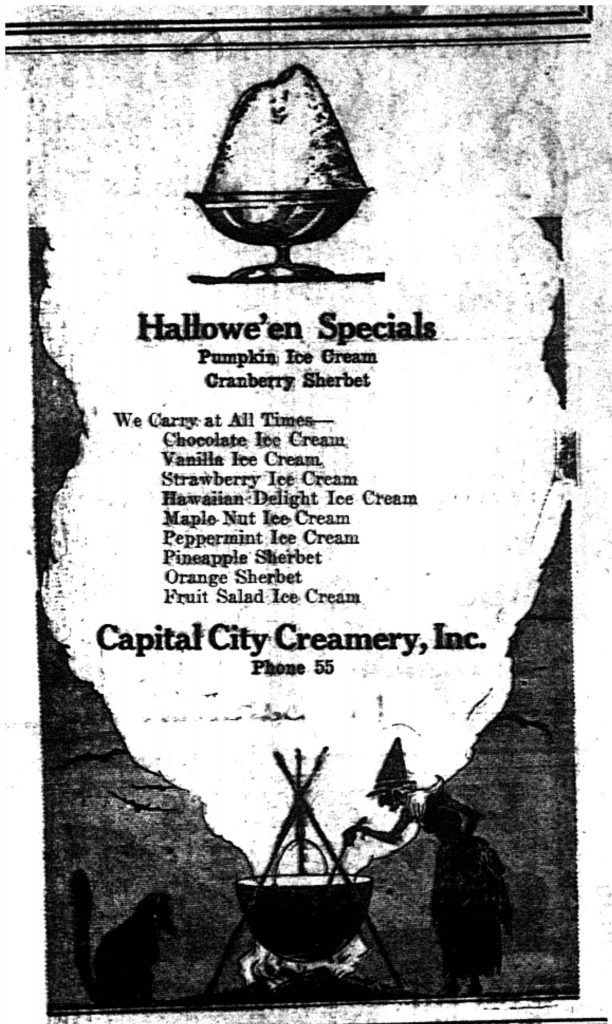

Halloween’s origins trace far back into history. All Hallow’s Eve is the night before All Saint’s Day, a celebration of the faithful dead still commemorated by the Catholic and some Protestant Churches. It replaced pagan Celtic new year festivities, adapting and changing folk traditions over the centuries. In early 20th century, United States Halloween was widely celebrated more for fun than anything else. It was usually spelled Hallowe’en at the time.

Around 1900 Olympia newspapers made frequent mention of Halloween mischief. Police issued regular warnings against vandalism and property destruction around the holiday, increasing patrols in residential areas and sometimes arresting a few of the mostly youthful male crowd. “No one should complain at a few harmless jokes and a little amusement,” the editors of the Morning Olympian fretted a day after the holiday in 1895, “‘Boys will be boys.’ The difficulty is these matters are too often carried too far. People have been frightened into insanity and valuable property has been destroyed through Halloween midnight depredations.”

Photo courtesy: Washington State Library

Quite a number of “pranks” went too far. Stealing gates, tearing up wooden sidewalks, even greasing the street car track (on steeps hills in 1912) could get expensive to repair. In 1901 three young men were arrested after being caught in the act of attempting to toss a sign into the bay. They were let off with a warning. In 1902, pranksters stole three carrier wagons from the Richardson shingle mill, forcing the mill to close until the equipment was returned. The owner, H.G. Richardson, offered a $50 reward for the thieves’ apprehension and the return of his property.

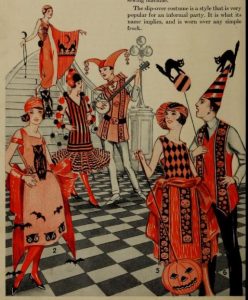

By the 1910s and 1920s things were changing, with pranking being largely replaced by parties in the days and weeks before the holiday. “Many of the young folks will haunt the streets and house yard in sheet and cap, or carrying goblin heads [jack-o-lanterns] to affright the timid, and the tick-tack [stick to tap windows with] will send its spooky message” the Olympia Daily Recorder reported on Halloween 1913, but then described the parties planned that night.

In 1920 the change in celebrating Halloween had definitely taken hold. Newspapers were full of reports of Halloween themed parties in the weeks preceding the holiday, complete with games and fortune-telling. There is a long history of fortune telling played by young women used to playfully determine the identity or profession of their future husband (or if they will wed at all). This included leaping over candles or bowls of water, popping nuts in the fire, or even peeling apples.

Schools held Halloween parties. Saint Martin’s College (now University) had a party for students and their friends with music from the college orchestra and games. Roosevelt School teachers held a party for their students with a witch fortune teller and served pumpkin pie and coffee for desert. (By the way, a can of “eastern” pumpkin cost 10 cents at Howey’s Cash Grocery according to a Morning Olympian ad on October 9, 1920). Olympia High School sophomores had a masquerade dance. A boy dressed as Rip Van Winkle won the costume contest. Costumes at the time were usually homemade, and the few commercially available ones were made of crepe paper.

While the largest parties were probably ones put on by the Woman’s Club of Olympia, Odd Fellows and Masons, a party organized by the Eligithin Campfire girls showed more of the Halloween traditions. Hosted by Dorothea Leach at her family’s home on Washington Street, the house was decorated with pumpkins, witches and autumn leaves. They had a bonfire, popping corn and roasting chestnuts, while also telling ghost stories. At one point, the hostess led a “ghost walk” outside.

Halloween was about to undergo another big change, with the popularization of trick-or-treating, replacing midnight mischief with door-to-door candy begging in costume. Helen Lord Lucas, daughter of banker C. J. Lord, recalled years later in a document at the Washington State Library how her mother Elizabeth got crowds of hundreds of children visiting her home at Halloween, giving them candy bars if they did a trick: “Some sang little songs, some recited poems, told jokes and asked riddles. One little boy stood on his hands and turned somersaults in the living room….When they had performed Mrs. Lord gave each of them a candy bar.”

Halloween has continued to change over the years, but it remains a beloved American holiday celebrated by many.