Submitted by Dr. Geoffrey Ankeney for Kaiser Permanente

Imagine riding in the New York subway when the train comes to a dramatic stop and a voice filters through the loudspeaker stating, “Sorry, folks. We’re stuck. Subway tube’s filled with jello. Might want to let your destinations know you won’t be showing. Then take a long nap. We’ll be here awhile.”

Physiologically speaking, I’ve just described a heart attack or a stroke. In this simple analogy, the subway tube is an artery, the people on the train are oxygen-carrying red blood cells, the unreached destinations are heart and brain tissue that will soon be dying, and the jello is a blood clot.

One of the big advances of 20th century medicine was in discovering the cause of strokes and heart attacks. Arguably, it was the remarkable German pathologist Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902) who got things off the ground by identifying that blood can form small clots that block arteries.

These days we understand that most heart attacks and strokes are caused by a gooey, rubbery (jello-y) mass called an atherosclerotic plaque that is stuck to the inside wall of an artery. Plaques are composed of fat, cholesterol, calcium and other blood components. Usually the plaques build up over years due to genetic predisposition or due to the impacts of poor eating, minimal exercise, and exposure to the physiologic effects of smoking, high blood pressure, obesity, and diabetes.

By itself, a plaque isn’t often a major problem. But plaques are prone to rupture, at which point blood starts to clot as it comes I contact with the inside of the plaques. If the clot grows big enough, a complete blockage occurs and the downstream tissues quickly start to die.

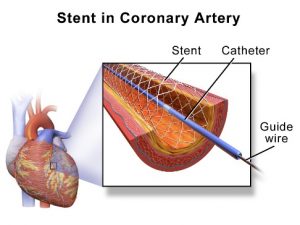

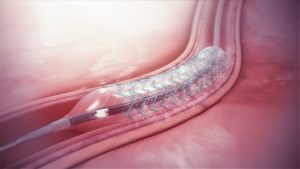

Back to our subway analogy: let’s say that as you’re waiting there in your seat, anxious to make your important meeting at Madison Square Gardens, a team rushes by your window. They’re carrying a long wire that they jam into the center of the jello mass in front of the subway train. Shortly thereafter, the wire magically expands outward in a metal lattice. It pushes outward, squishing the jello material against the subway walls. They then disconnect the wire, leaving the lattice in place. You now have a nice open subway again. The train moves forward. You deliver a spectacular performance singing “Piano Man” to a rapt and appreciative crowd.

The subway story is describing a relatively newer approach to blocked arteries, the stent. Although stents are used in situations throughout the vascular system of the body, coronary stents are the most common. The first to use one was Jacques Puel and Ulrich Sigwart in Toulouse, France in 1986. Things took off quickly from there, with the first FDA-approved stent entering the medical system in 1993.

The first stents weren’t stents at all, actually. They were balloons. A wire was pushed through the blood clot and a balloon inflated, then removed. As you might expect, the ruptured plaque quickly blocked things up again. Then the bare metal stent was introduced which is in some cases still used today. But the bare stents often pick up blood clotting factors and also block off over time.

These days the most common stents are called “drug-eluting stents” because they slowly release a drug to block cell proliferation and fibrosis. The DES’s are shown to have lower rates of major adverse cardiac events like heart attacks and re-interventions due to new blockages.

As with any procedure, there are risks to stent placement. There’s also some question about whether or not a stent is superior to bypass surgery, although there is no question it’s less-invasive. There are a number of randomized studies ongoing comparing the two procedures.

So, stenting isn’t for everybody. But when used for the right people, it can save lives and markedly improve the quality of life. Compared to some medical technologies, the procedure is still in its infancy. We still need to know more about how the stents affect the body, and if they really extend the lives of people with cardiovascular disease. But most indications are that they do extend life, they do it well, and at a fraction of the trauma caused by surgery.