In focusing on tribal communities, policymakers and educators tend to look at what’s missing. That, according to Nisqually Indian Tribe Interim Education Director Bill Kallappa, is a misconception. “Native communities are asset based,” he says. “There’s a lot that we can give to the public school setting, whether that’s history presentations or sharing our culture with students in the K-12 system. Often, people want to look at deficits when we really have things to contribute.”

Now Kallappa will be sharing those contributions and perspectives with the State Board of Education. He was appointed by Governor Jay Inslee in February 2019 and will serve on the board through 2023. “I’m honored and I’m humbled to have been appointed to this position,” says Kallappa. “I take it very seriously and I see a lot of improvements that can be made to our K-12 system, not just for native students.”

Now Kallappa will be sharing those contributions and perspectives with the State Board of Education. He was appointed by Governor Jay Inslee in February 2019 and will serve on the board through 2023. “I’m honored and I’m humbled to have been appointed to this position,” says Kallappa. “I take it very seriously and I see a lot of improvements that can be made to our K-12 system, not just for native students.”

Looking at his career thus far, this opportunity seems like a culmination of his many varied experiences. A Makah tribe member, Kallappa grew up on the Skokomish Reservation and attended Shelton High School. From the beginning, he was drawn to working with native youth. “My first job was as a summer day camp counselor on the reservation,” he says. “I’ve always enjoyed it.”

Later, his experience as a para-educator working with special education students inspired him to return to school and get his bachelor’s degree at age 30. He was on track to get his master’s degree in teaching when his daughter was born, and that goal went on hold. In the meantime, he worked with both the Skokomish Tribe and Squaxin Island Tribe doing drug and alcohol prevention programs, youth activities, and camps.

And then there was coaching. Wherever he goes, Kallappa brings a passion for teaching kids how to play sports, including football, boys and girls basketball, and track. He co-founded the Inter-Tribal League (ITL), an organization that provides tribal youth in grades 3-12 with access to sports such as basketball, flag football, and soccer.

“We draft a schedule and get the kids out on the floor with the uniforms and the buzzer and grandma and grandpa cheering,” he says. “We know that if kids are participating in extracurricular activities and sports, attendance goes up, behavior is better, graduation rates go up, and dropout rates go down. Now we’re seeing more kids playing for their schools in all different sports.”

Another key program: youth councils. He first became involved with the United National Indian Tribal Youth (UNITY) organization as a teenaged youth ambassador, doing outreach to other students. He has since helped to establish youth councils in Skokomish, Squaxin Island, and Nisqually. “They have constitutions, bylaws, and elected officers,” says Kallappa. “We meet once a week and they go over their agenda.” Tribal leaders like Nisqually’s Willie Frank III support the students in an advisory capacity.

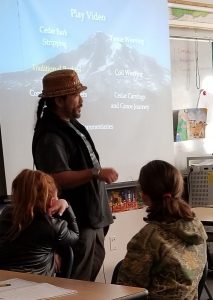

After the Since Time Immemorial curriculum became mandated by state law, Kallappa and Nisqually tribal members developed a collaborative relationship with Yelm and North Thurston School Districts. “We did a professional development day for River Ridge High School staff about a month ago, and that was amazing,” Kallappa says. He, Franks III, tribal council member Hanford McCloud and his mother Joyce McCloud shared lessons on this cultural significance of the drum, treaties, and more recent history like the Boldt Decision and how it impacted fishing rights.

“With STI, the curriculum is great but there are still a lot of teachers that don’t know the history themselves,” says Kallappa. “They never learned it when they were in school. So it’s up to as tribes to participate, to come in and share so that teachers don’t feel like they’re teaching the wrong thing or teaching it from a different point of view. We’re trying to get into more schools.”

Aside from his other roles, Kallappa represents the Governor’s Office on Indian Affairs (GOIA) as a member of the Education Opportunity Gap Oversight and Accountability Committee (EOGAC), a legislative body that includes commissions of people of color. “We’re really trying to close the achievement and opportunity gaps that exist in our system,” he says. “I see my role on the state board as representing students of color, low-income students, those with learning disabilities and different physical abilities, and foster care youth. If we can close the gaps for that body of students, it’s going to elevate the whole system.”

He’s concerned that the current emphasis on standardized testing and increasingly demanding graduation requirements, particularly the idea of a final graduation exam, will sideline many already marginalized youth. “They’re the ones who are going to have a hard time with the test, when really they’ve already done a body of work that demonstrates enough to graduate from high school,” he says.

Once on the board, he’s looking forward to having tough conversations that create real change. “If you’re trying to make a paradigm shift institutionally, we need to look in the mirror and say, ‘Are we really doing right by our kids?’” he maintains. “Our kids aren’t failing us, we’re failing them.”

When the Governor’s office came calling, Kallappa’s first stop was the Nisqually Tribe, whom he asked for permission to join the board. “I’m honored to work for a place that allows me the space to do this work, knowing that it can impact not only Nisqually kids but native kids, students of color, and foster kids across the state,” he says. “I feel really lucky to work for an organization that allows me to do that.”

To learn more about the Nisqually Tribe, visit their website.