Early one chill morning on February 17, 1912, the men of the Hercules Sandstone Company and Dupont Powder Company went about checking and rechecking their work, poking their heads into the explosive-filled coyote holes dug deep into the hillside at Hercules Quarry #2 in Tenino. And though their breath hung in the air, the nervous sweat and tension hung heavier.

These men were professionals, but few had ever attempted a blast of this magnitude and with so many eyes watching. Meanwhile in Seattle spectators and officials from the Army Corps of Engineers boarded a southbound train to Tenino. For them the day promised a bit of excitement, a front row seat and the prospect of a celebratory meal afterward.

These men were professionals, but few had ever attempted a blast of this magnitude and with so many eyes watching. Meanwhile in Seattle spectators and officials from the Army Corps of Engineers boarded a southbound train to Tenino. For them the day promised a bit of excitement, a front row seat and the prospect of a celebratory meal afterward.

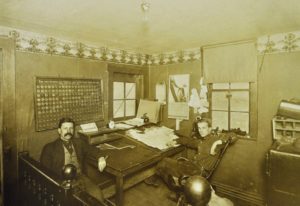

The actual feelings of the company men on that day are only imagined and lost to history, but it is not hard to imagine what was at stake. The Hercules Sandstone Co. was reaching a crossroads. In business it is all about supply and demand. And if the world should no longer want what you offer then it is time to innovate and try something new, radical even.

The bread and butter of Tenino-produced sandstone was its precision cut stone used in construction. But by 1910 steel girder construction, rising higher and higher into the skyline, relied on revolutionary, on-site mixed concrete. Why pay to have stone cut and shipped when it was more economical to bring in a rotary mixer or cheaper concrete blocks? So Hercules Sandstone Co. needed to find a new market and possibly an innovative product.

The Army Corps of Engineers announced its need for large sandstone boulders to be used on a jetty at Grays Harbor. Hercules Sandstone Co. put in a successful bid and consequently purchased a quarry off of Old Military Road, formerly owned by the Eureka Stone Company. The new quarry, called Hercules Quarry #2, would be used to produce 375,000 tons of large, rough boulders to be delivered to Grays Harbor from 1911 to 1912. Blasting was thought to be the most efficient way to get the job done.

As Scott McArthur, grandson of Hercules superintendant William McArthur, wrote in his book Tenino Washington The Decades of Boom and Bust, “This was the first rubble stone contract entered into by the Hercules Sandstone Co. and marked the beginning of the end for the company.”

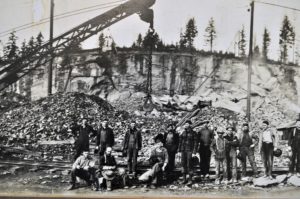

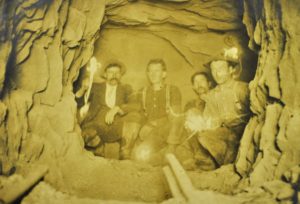

At Hercules Quarry #2 they dug 1,400 linear feet of three-foot wide tunnels known as coyote holes. Blasting experts from Dupont, Washington’s Dupont Powder Co. wired and packed the tunnels with 43,100 pounds of black powder and 1,200 pounds of 60 percent dynamite.

The Centralia Weekly Chronicle wrote, “The blast will be the biggest event in the history of Tenino, and the city is preparing to entertain several thousand visitors on that day.”

When the train from Seattle arrived loaded with spectators, there were also among the lookers-on reporters and a camera crew from the Motion Picture Advertograph Co. of Tacoma. Scott McArthur wrote, “Folks in Tenino were warned to take all their fragile possessions down off the shelf. At 2:25 o’clock that afternoon, Major J.B. Cavanaugh of the Army Corps of Engineers….pressed the electric button. The charge was fired.”

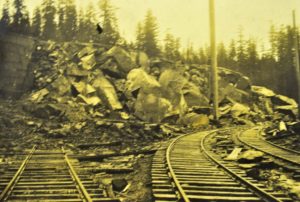

Some accounts say it was the largest single explosion in Washington State history. The Seattle Daily Times wrote, “What probably was the biggest single blast ever discharged in the United States took place at the Hercules quarry at Tenino this afternoon when more than 500,000 tons of sandstone were broken up by a single charge of 50,000 black powder and dynamite.”

It may be that some newspapers of the time were prone to hyperbole for The Morning Olympian wrote, “Its most unique feature was the almost absolute absence of any noise or concussion. The load was so arranged by expert engineers that the noise and danger was minimized, scientific care being exercised by everyone employed.”

However, McArthur wrote that the town shook, a huge cloud of smoke and dust arose in the air, the railroad spur leading to the quarry was buried under rubble and holes up to 10 feet in diameter were punched in the quarry’s buildings.

While the blast was exciting, the ensuing official celebration attended by 102 persons is also notable. McArthur wrote, “25 men – only one from Tenino – were listed as giving speeches. The dinner menu was a monument to boosterism. It featured: Olympia oysters (cocktailed with Tenino booster spirit), consommé a la Sandstone, chicken (with Hercules sandstone noodles), cold roast (with Sea Board oil), browned potatoes (with crushed steel), celery and lettuce (grown on Mount Mullaney), lemon pie (Keithahn Cream with DuPont powder cakes), tea, coffee, wine and homespun cigars (of Hercules strength).”

And while everyone was impressed with the events of the day, 40% of the blasted stone was crushed beyond usefulness for the jetty project, and the expense of cleanup did not help matters. But despite everything the Hercules Sandstone Co. still managed to deliver 387,000 tons of stone from 1911 to 1913. When the time came, however, the contract for the Grays Harbor Jetty was not renewed.

Subsequent government projects of this nature were not enough in the long run to sustain Hercules. In January of 1916, government funds were frozen and projects suspended because American involvement in World War I was imminent.

Further Reading about Tenino Quarries:

- McArthur, Scott, Tenino, Washington: The Decades of Boom & Bust (Monmouth, OR: Scott McArthur, 2005).

- Dwelley, Arthur G., Prairies & Quarries: Pioneer Days Around Tenino 1830-1900 (Tenino, WA: Independent Publishing Company, 1989).

- Tenino – Thumbnail History

- Tenino, Washington by Miss Blendine Hayes

- The Tenino Stone: One of the big three Washington state building stones