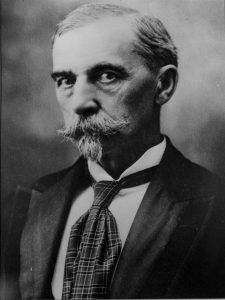

In the shadow of the Old State Capitol in downtown Olympia stands one of Olympia’s few historic statues. It is a monument to John Rogers, Washington State’s third governor. Why and how he was honored is a remarkable story.

John Rankin Rogers was born September 4, 1838, in Brunswick, Maine. He moved around the country, farming, teaching school and working as a pharmacist before finally settling in Kansas. In Kansas, Rogers became active in Populist politics. Populism was an agrarian political movement that sought to help farmers and curb the power of financial elites.

In 1890, John Rogers and his family moved to Puyallup where he opened a grocery store with son Edwin. He was elected to the Washington state house of representatives in 1895 and soon became famous for his educational advocacy.

The state school system was in its infancy. While the state’s 1889 constitution emphasized the importance of education, funding schools was a different matter. The constitution allowed for a state tax to fund schools, but it was undefined and not imposed. Paying for schools included some state funding, but was left largely to revenue raised by the individual districts, which created a large gap between small impoverished rural districts and wealthier urban districts.

Rogers felt this was unfair. He introduced House Bill 67, which called for a direct tax on real property that would provide schools six dollars minimum for each school-age child living in the state, thus help equalizing education between poor and rich districts. Although the bill faced opposition from major cities (which already taxed inhabitants for schools), it passed. Somewhere it earned the nickname the “Barefoot Schoolboy Law,” since the poorest students often did not have shoes.

In 1896, the state was crippled by economic crisis and people wanted something different. The Fusion Party, a collation of Populists, Democrats and Silver Republicans swept into office, putting forward Rogers, made famous by his school bill, as its candidate for governor. Adding a third party to the election divided the vote and Rogers only became governor with a plurality of 12,000 votes. He took office in 1897.

As governor Rogers proved an honest and capable administrator rather than a firebrand. The economy began to recover with the 1897 Alaska Gold Rush, as the state was able to supply miners going north. Economic recovery weakened support for the Fusion Party.

Still, Rogers was reelected in 1900, this time as a Democrat. Economic recovery brought many Republicans back into office, however, and they won control of both houses and all state offices except Governor and were able to block his projects.

Rogers’ sudden death from pneumonia on December 26, 1901, shocked people. The legislature even voted to send money to support Rogers’ widow.

Others wanted a more lasting way to honor him. Lead by J. M. Lahue of Puyallup, teachers at the Pierce County Teachers’ Institute (an annual meeting of teachers) called for a monument for Rogers. They formed a committee of people from across the state and raised $2,500 through popular subscription, including school children. The group decided to erect a statue in Olympia at Sylvester Park, located in front of the then State Capitol. It took over a year to raise the funds.

Seattle’s New England Granite and Marble Company was picked to create and install the monument. In early December 1904, the statue committee in consultation with Governor Rogers’ widow Sarah Rogers and their daughter Caroline Blackman picked a final location for the statue directly in front of the Capitol. The New England Granite and Marble excavated and put in a concrete foundation. The statue and its base were brought down in pieces on the steamer Multnomah from Seattle. Because of the statue’s weight, the ship could not dock. The pieces had to be removed to a lighter (barge) and towed in to the foot of Main Street (now Capitol Way), before being transported up to the park.

The statue of Rogers was dedicated on January 19, 1904. Several hundred people gathered as the committee spoke as well as Governor Albert Mead. John R. Rogers, Rogers’ grandson, unveiled the statue. The Oregonian newspaper account adds a poetic shaft of light hitting the statue at the moment of unveiling on an otherwise cloudy day.

The statue was not quite complete. Its inscription, written by Alden J. Blethen (Seattle Times editor and friend of Rogers), needed to be redone. Blethen originally described Rogers as a “plebeian, philosopher and statesman.” The carvers spelled plebeian as “plebian.” Final payment was held up until F. L. Crosby from Seattle replaced the misspelled word with an uninscribed panel and scroll.

The Rogers statue became a landmark of Sylvester Park, featured in countless postcards and photos. The motto on the statue still sums up John Rogers life. “I would,” it quotes, “make it impossible for the covetous and avaricious to utterly impoverish the poor. The rich can take care of themselves.”