It’s no secret that farming is hard work. The days – and sometimes nights – are long and spent tending to the land and animals. In inclement weather, at inconvenient times, farming waits for no one. If you don’t come from a long line of farmers, as is the case with Rachael and Matthew Tuller of Lost Peacock Creamery, starting up a farm – and making a living wage – can be a daunting task at best. There’s little that can prepare the uninitiated for the rigors of farming, except for one thing, Rachael says, and that’s the military.

It’s hard to fully understand what farming entails unless you’re in it. By reading a book, you can’t smell the sweat on a farmer after they’ve been up all night working to save an animal, and when talking to them, they probably don’t gush about the endless stream of tears that happens when their efforts don’t succeed.

It’s hard to fully understand what farming entails unless you’re in it. By reading a book, you can’t smell the sweat on a farmer after they’ve been up all night working to save an animal, and when talking to them, they probably don’t gush about the endless stream of tears that happens when their efforts don’t succeed.

The same can be said of military service, too. Veterans bravely share their stories of service and we try hard to be empathetic listeners. But unless we’ve also served, we never truly understand.

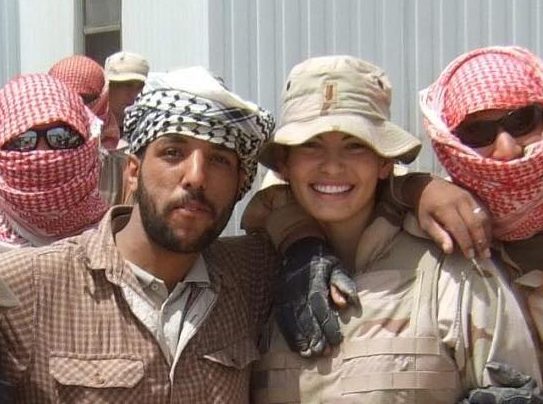

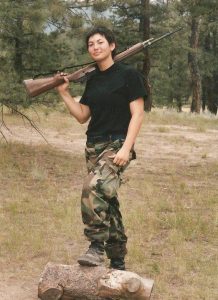

Rachael Tuller is a first-generation farmer and United States Air Force veteran who’s worn both the Airman combat uniform and a pair of overalls. She entered the Air Force Academy in 2001 and commissioned in 2005 as a Second Lieutenant. She was a services officer with a focus in readiness deployment and mortuary who deployed in 2007 in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. She was based out of Balad Air Base in Iraq as a protocol officer.

Rachael comes from a long line of airmen, not farmers, and her grandfather served in the Air Force as a gunner, her father as an F -15 fighter pilot. Rachael’s father, Mac McIntosh, whom Rachael describes as “the greatest fighter pilot who ever lived,” also graduated from the Air Force Academy and Rachael grew up as a self-described “military brat.”

Military and serving our country are a big part of Rachael’s foundation, but after separating from the military, she sought a deeper connection. She had a good nine-to-five corporate job, but also a crazy dream to be a farmer. A certified grade A dairy goat farmer, at that.

Rachael did two years of therapy through Veterans Affairs after she transitioned back to civilian life, and says, “It wasn’t until I started my own farm that the tools I was given in therapy started to make sense and click in my brain.”

A member of Farmer Veteran Coalition, she also received her farm loan through Northwest Farm Credit Services, which is a big part of the Farmer Veteran Movement.

Rachael attributes many of the virtues she learned in the military to her success as a farmer and she details how being able to “shut up and color” has influenced her as a farmer.

Shut Up and Color

“This is a phrase we had at the Air Force Academy,” she says. “It basically means quit your whining and just do it. Farming requires this mindset more often than not. A fence that needs to be repaired in the pouring rain, a barn full of pregnant animals that need to be checked in the middle of the night in the freezing cold, cheese that needs to be hung at 1:00 a.m. It doesn’t do any good to whine about it. Just do it. Shut up and color.”

Getting Good at Erratic Schedules

Rachael says when you’re in the military, you never actually own your time. “Even on a weekend,” she says, “unless you’re on leave, you can be called in to work.” Already adapted to that mindset, she transitioned easier into farming where you also never really own your time.

“Time is dictated by the work and the seasons of the farm,” she explains. “You can’t just push something back because you don’t feel like it. When it’s time to do something on a farm – it’s time to do it.”

Managing Stress and Dealing with Change

There is one constant in the military, and it’s that is change is inevitable. The same can be said of farming.

“Just when you think you’ve hit a groove, something changes,” Rachael sighs. “I’ve often said farming is just one sucker punch after another. The military is like that too,” she says, and managing the level of stress and anxiety that comes with being a farmer and a small business owner is monumental.”

Understanding Death

“As a mortuary officer, I worked with family members of the deceased,” Rachael says, “and the actual deceased service members. It was honorable and noble work. I am infinitely grateful and proud to have been a part of it. It was work that prepared me for the inevitable death that comes when you farm with animals.”

Building Community

Serving in the military usually equals a transient lifestyle, and service members learn to build community wherever they are sent.

“Farms, in their most robust state, also build community,” Rachael shares. “One of our main goals at Lost Peacock Creamery is to be a part of our community, which means that we know the people eating our food and they know us. This farm is an ever-evolving piece of land that is working towards an educational model that encourages and inspires others who dream of farming to take up their own shovels and start the work.”

Lost Peacock Memorial Garden

The Lost Peacock family farm is ever-expanding, and Rachael’s mother, Linnea McIntosh is now homesteading the land next to the Tullers’ farm. The McIntosh-Tuller clan has worked hard to create a Memorial Garden on their land honoring family members who have passed before them. Linnea created the garden as a form of grief therapy after her greatest-fighter-pilot-husband-and-father-who-ever-lived fell in his final battle with pancreatic cancer.

“The garden has plaques and benches,” Rachael says, “and a mailbox for the kids to write notes to their ancestors, and spaces for them to leave gifts for the dead. It’s a place to talk about, laugh about and remember those who have died before us. We have nine family members honored in the garden now.”

Farms are a place of toil, but also a place of healing, as Rachael from Lost Peacock Creamery illustrates. She shares openly on social media about real farm life, not just the pretty stuff, (although from her stunning photography you’d think that farming is all glory).

Read her poignant, yet honest words about farming on her blog, or watch her give a keynote address at the Thurston County Chamber’s Thurston Green Awards.