The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest public health concerns of our time. At least two million people come down with an antibiotic-resistant infection every year in the U.S. Of those infected, approximately 23,000 will pass away as a result. You might be surprised to find out that one solution to the problem may be in our own backyard at The Evergreen State College Phage lab.

Phage is short for bacteriophage. A bacteriophage is a virus, which is specific to bacteria and other single celled organisms. Prior to the widespread use of antibiotics, phages were being used to treat many types of bacterial infections around the world. Following World War II, phage therapy and research became less common in the United States, but other countries continued to use and research phages to treat disease. Now, with multidrug-resistance strains of bacteria, interest in phage therapy has renewed around the globe.

Dr. Elizabeth Kutter, or Betty as she is known around Evergreen, has been working on phages since the 1970s. Her work has brought a number of prestigious grants to the college for scientific research, including grants from the National Institute of Health. Though she officially retired nine years ago, Betty remains engaged on campus, passing on a wealth of knowledge to new generations of students every year.

Applications for phages therapy are broad. Phages can be applied in food safety, water treatment, infection treatment in burn victims and have been used to treat infection in diabetic skin ulcers as well. Diabetic ulcers, especially in the feet, can be difficult to treat with traditional antibiotics because of reduced blood circulation. Phages transmit between the bacteria, so they are not as reliant on the circulatory system as many antibiotics.

Betty doesn’t think phages will replace antibiotics. Instead, she thinks that they will be another option when antibiotics don’t or can’t work.

“I think phage therapy could be a useful tool in conjunction with antibiotics to treat infections,” says Betty. She points to a recent case where a medical college professor had a resistant bacterium that eventually put him in a coma. After all FDA approved methods were exhausted, the patient’s life was saved by phages from the U.S. Navy.

A major benefit of phages is their specificity, meaning they focus on only one or two strains of a specific bacterium species. Many antibiotics kill off all or most types of bacteria at once, taking the good with the bad. For instance, they don’t discriminate between non-pathogenic staphylococcus and pathogenic staphylococcus bacteria. Killing off all the good bacteria can cause worse problems for the patient down the line, especially patients with already weakened immune systems. Phages have been isolated that affect very specific strains of bacteria, and target only those strains. Recent phage research has been promising with E. coli H0157, a bacterium with highly toxic effects that cause food poisoning.

Students of Betty have gone into graduate programs in phage research around the county and world, advancing the science in new and exciting ways, and it all started with their work at Evergreen.

Betty doesn’t let retirement slow her down. She shares her knowledge with the scientific community, flying around the world to work with other researchers, students and medical professions to advance global understanding of phages. The phage lab of Evergreen has built collaborative relationships nationwide with other laboratories working in phage research from Cornell to UC San Diego.

Collaboration extends internationally as well. Betty just returned from conferences and speaking engagements in Belgium and Russia where she worked with people from many different countries.

“There is a lot of phage research and application in countries like Georgia and Russia,” she says. “You can walk into a pharmacy there and walk out with a box of phage.”

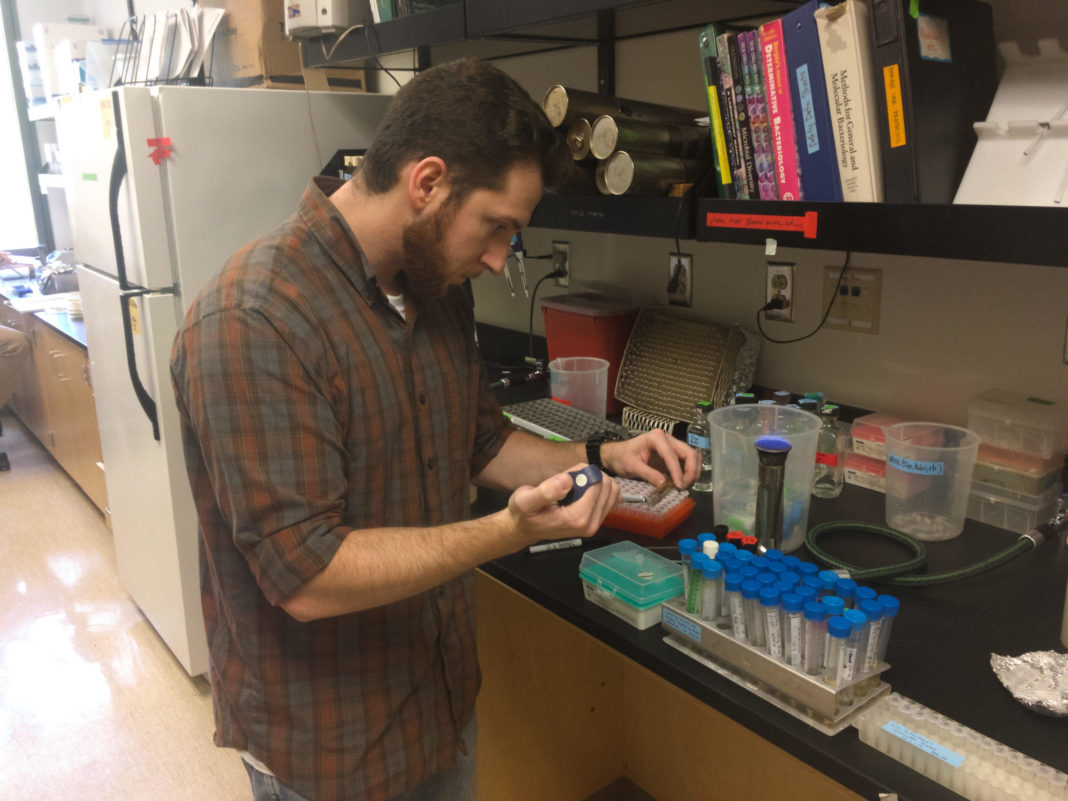

When Betty returned from her trip, she brought different strains of phages back to the lab at Evergreen. Now the students are working on isolating each strain for research.

Phage research is promising; however, research and approval, especially in the U.S., is difficult. The testing and approval process that was created for drugs, not viruses, can be difficult, and doesn’t translate well to phages. Unlike antibiotics, which are chemicals used to inhibit certain growth processes of bacteria, phages are viruses, which multiply within the bacteria and spread at rates that are difficult to calculate and demonstrate in tests in patients. Betty believes with renewed interest, those hurdles can be overcome.

Not only are Evergreen students working in the phage lab, three high schoolers from Olympia High, Capitol High and a private school in Tacoma work in the phage lab, learning about this cutting-edge science, informing and inspiring their future careers.

Through research, testing and collaboration, knowledge and understanding of phages grows year after year, but there is still so much to learn.

Exciting educational opportunities are available at Evergreen. To find out more about the different areas of study available, take a look at The Evergreen State College website.

2700 Evergreen Pkwy NW, Olympia

Sponsored